Victor Hugo's hairdressers

25th October 2016

In Guernsey in 1858 Victor Hugo became seriously ill with anthrax. It was apparently after recovering from this near-fatal illness that he was persuaded to grow a beard, as a protection for his throat; the first photograph of him sporting a beard was taken on 5 May 1861 on a visit to Brussels, during his trip to finish Les Misérables. For a while he allowed it to grow luxuriantly, but soon smartened it up and adopted the shorter beard now so familiar from photographs. Above is a portrait of one of Hugo's hairdressers, James Le Gallez, by kind permission of Ann Philippo. This is part of the Victor Hugo and Guernsey project. [By Dinah Bott]

Blicq’s

It was Mr [Frank] Blicq’s father who was hairdresser to Victor Hugo. He established his little shop in Tower Hill in 1847, after serving an apprenticeship with Mr Dupuy, a hairdresser at Quay Street. The story goes that the great writer had two characteristics noted by his barber: a mop of hair and a morose silence. [On the occasion of Frank's retirement, aged 72.]

[Guernsey Weekly Press, 10 March 1938.]

Blicq’s barbers made the corner of Tower Hill and Hauteville and there the great French poet was a regular customer. When he was seated in the barber’s chair, curtains were drawn around him. The shorn hair was burned on the spot, but the beard trimmings were saved. Hugo took them away so that they might be preserved in the pillow of his mistress, Juliette Drouet, who lived at Beauregard, a stone’s throw from Hauteville House.

[Guernsey Press, 19 October 1979.] (A Bourde de la Rogerie attributed this strange habit instead to Hugo’s wish to avoid the souvenir hunters.)

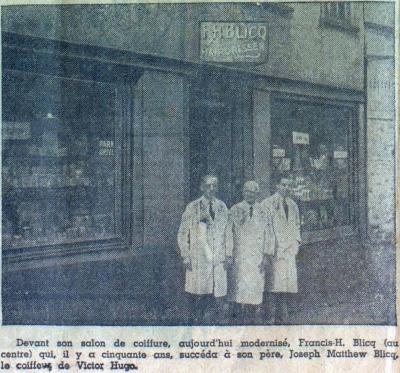

The photograph is from an article by Pierre Cressard in L'Ouest-Eclair, 22 November 1936. The same photograph can be found in Coysh & Toms's book, Old Guernsey in pictures, no. 87. A portrait of Frank Blicq, perhaps dating from his retirement in 1938, was published in Toms' St Peter Port, People & Places, Phillimore, 2003, in the Library, p. 114. According to Toms, the salon opened in the 1860s (90 years previously). However, see Cressard below.

Victor Hugo at the hairdresser

On the way up to Hauteville House, half-way up the heights that overlook St Peter Port, there is, perched at the top of the steep steps of Tower Hill and flattened up into a corner against the cliff, resembling an enormous piece of cake, a bizarre and picturesque building. It was there in 1840 that a young Guernsey hairdresser, Joseph Matthew Blicq, opened the doors of his hardresser's shop for the first time. When I say doors, I am not exaggerating, as the new shop had no fewer than five. It was an odd shop, triangular in shape, 9 x 7 feet, with a no furnishings except a simple counter where Mrs Blicq took the money, at the same time feeding her newest-born under her shawl, and a sort of doctor's chair for the first in the queue. Everyone else had to stand and wait near the fireplace where the copper kettle bubbled away. From break of dawn until evening, by candlelight, Joseph Blicq worked his scissors unceasingly to bring up his large family—he had no less than fourteen children. The English gentry of Hauteville all streamed through this humble salon, having their hair cut and beard trimmed for twopence, or a shave for a penny, where they would discuss the events of the Big Country, news brought from the harbour or island gossip.

One day, one of the five doors opened with a gust of wind, and in came, with the whirl of his greatcoat, a stocky man with a lordly bearing, eyes aflame, his beard bristling. It was Hugo, the great exile, the master of Hauteville-House, the thundering phantom from the haunted house. Conversation stopped dead. The customers froze, both shocked and respectful. The occpuant of the only seat in the salon had made way, deferential and with half a haircut. Hugo, without ceremony, had already installed himself in his place: 'Beard and hair!' Blicq, trembling and flattered, set about it; he risked a few words in French; the poet, who never liked talking in English, was won over, he and Blicq bcame friends, and until his departure from the island, Hugo remained the customer of the Guernsey Figaro. But Hugo always expected the same deference and, every time that the care of his luxuriant ringlets, or of his abundant beard, led him to the little shop, it was understood that the only chair was immediately vacated for him.

If by any chance inspiration smiled upon him in the mirror, while the scissors were squeaking away, then would they leave him be, and a paper and pencil would be quickly found for him; the poet would write, the poet would compose; Blicq would wait respectfully with his tools poised, while looking around at those present with an air of victory, for his salon seemed to him then to be as grand as a temple. The Muses prevent me from considering hinting even remotely that the verses written in the barber's shop might be exactly those which, in our schoolboy slang and lignorance, we used to call 'razors.' [i.e. boring.]

Howver, to avoid accusations of being a fantasist I feel I must report the exact words of Francis-H Blicq, the eldest son of J-M Blicq, who for fifty years now has run his father's business, at No 1 Hauteville, with its multi-coloured sign outside. If the Blicqs, father and son, exercised their profession of 'Hairdresser', handed down like royalty, there are no more patent letters of nobility for them than for fifteen years to have kept the custom of the great exile, Victor Hugo. In the salon, today enlarged and modernised, huge windows having replaced four of the five doors, the master of this interior, on the warm recommendation of my friend and colleague, Monsieur Pierre-Gabriel De La Mare, Sports Editor of the Guernsey Press, treated me with great regard and had me sit on the poet's chair, piously kept in a place of honour , where I copied these exact words:

In 1861, Hugo grew a beard to conserve his strength

Mr Blicq is not the only hairdresser in the island to have had the honour of attending to the wants of Victor Hugo. Mr Le Gallez of Fountain Street tells of his father, who owned a barber’s shop in Mill Street, and who was in the business for over seventy years.

Mr Le Gallez Senior, who died some years ago, had the distinction of being able to say that he was the last man to have shaved Victor Hugo. The poet, who had suffered for many months with a throat ailment, sent over to Paris for his own physician who, when he arrived here, recommended that the patient should grow his beard in order to ‘conserve his strength.’ That same day Hugo went in to Mr Le Gallez’ shop and said in French, ‘This is the last day that you will ever shave me. I am growing a beard. How do you think I will look?’

Some time ago Pierre Cressard, of L’Ouest Éclair, a French newspaper, paid a visit to Guernsey and interviewed islanders on their reminiscences of Victor Hugo. We read this connected with the first appearance of Victor Hugo at Mr J M Blicq’s hairdressing saloon, Tower Hill:

One day one of the doors opened as if blown in by the wind. And there was seen entering a man, broad-backed and hardy with the air of a grand Seigneur, his eyes as if on fire, and his face thickly bearded. It was Hugo, the great exile! Conversations ceased, the people within remaining in position respectfully and with a sense almost of awe. The occupant of the chair got away from it deferentially, though only half shorn of his hair! Hugo installed himself in the chair. ‘Beard and hair,’ exclaimed the poet to Mr Blicq. Mr Blicq nervously attended to the great head so thickly covered with hair, and risked a few words in French. Hugo was conquered; he did not like to attempt using the English language. And so the two became fast friends until the departure of the poet.

At times while his hair was being dressed, an idea would inspire Hugo, and work would be interrupted while he pencilled his thoughts on paper, and so the hairdresser’s shop became as a Temple of the Muses.

[Guernsey Press, April 1 1937.]

Victor Hugo always took a keen interest in Mr Le Gallez and his family and unfailingly on holidays such as Christmas and Easter he would say to the barber, ‘Well, how many children have you now?’ and he would thereupon produce a 5-franc piece for each of the children. In contrast to this generosity, he never gave so much as a sou extra for his shave, which was a penny in those days, or for his haircut, which was 2d.

The poet after a shave would ask for a large basin of water into which he would plunge his head completely, and then he would blow noisily into the water. One day, a customer coming into the shop, saw the ritual in progress, and not knowing who was in the chair, cried out: ’Hey, what do you think you‘re doing, drowning yourself?’

There were surely few occasions in the great man’s life on which he had been addressed in such a familiar manner.

[Guernsey Press, 1937. James Le Gallez, 1832-1919, son of Pierre Hilary Le Gallez and Martha Lihou.Photograph by kind permission of Ann Philippo, a descendant of James Le Gallez.]

It is said he would collect all his hair and shaving clippings [from Le Gallez’ shop], place them in a bag and then take them home.

[Guernsey Press, 3 March 2004.]

Hugo played draughts with James and they enjoyed a happy friendship (information courtesy of [James Le Gallez'] descendant, Ann Philippo.) [Cox, G S, Victor Hugo's Guernsey Neighbours, Toucan Press, Guernsey, 2015, p. 23]

On 27th October 1864 François-Victor Hugo wrote a letter from Brussels to his Guernsey-born fiancée, Emily de Putron, in which he described the hotel in the village of Mont-St-Jean where his father stayed on the 1861 trip as having a sign-post outside bearing the following inscription: 'In this hotel M Victor Hugo lodged for several months. It was indeed here, and on the field of battle, that he finished the famous novel, Les Misérables.' [Dans cet hôtel logea pendant plusieurs mois M Victor Hugo. C'est ici même et sur le champ de bataille qu'il finit le fameux roman, Les Misérables.]

The first page of this letter, which contained these words transcribed in capitals by François-Victor, is now lost; at the beginning of the century the letter belonged to Alfred Naftel, an Guernsey antiquarian and collector of Hugo memorabilia, and we have only his description of it and a poor-quality part photograph. The remaining page of the letter is still in a private family collection in the island.

The photograph of 5 May 1861, which was thought to be the work of the famous photographer Pierre Petit, has recently been attributed to Gilbert Louis Radoux, a fellow exile who had found his way to Belgium and who was an architect by training.