Early children's books

The Priaulx Library has amongst its collection of rare items several books intended for children.

These fragile volumes took some very heavy treatment from little hands and it is unusual to find any in really good condition.

The American Libraries Internet Archive has digitised copies of several of these books available to view online. Most of the texts of the books originated in Britain but were sold on to American printers and publishers, who often made changes, particularly to the illustrations.

Probably the earliest book in the collection is an incomplete copy of The Picture Exhibition: containing the original drawings of eighteen little masters and misses: to which are added moral and historical explanations.

The American Libraries Internet Archive's copy is certainly much cleaner and easier to read but may be a very much later edition; our volume is missing the end papers which list other books for sale and help to date the American edition. The Picture Exhibition was put together by Richard Johnson (1734-93), who was editor, compiler, and sometime writer of a number of children's books. He also produced his work under pseudonyms (and was not above copying and plagiarism). In this book he has gathered together eighteen paintings and written a story to accompany each of them; the introduction purports to come from the author, the respected 'professor of painting' P. P. Rubens (a.k.a. Richard Johnson). The stories are certainly written to give moral guidance but are not without humour. Johnson also illustrates the books himself; he was probably the illustrator of the first edition of The History of Little Goody Two Shoes, published by John Newbery, with the text by Newbery or Oliver Goldsmith, perhaps the most influential children’s book of its time. Amongst his other works are Juvenile Sports and Pastimes (1776), by 'Michael Angelo' and Poetical blossoms. Being a selection of short poems, intended for young people to repeat from memory (1793). By 'the Rev. Mr. Cooper.' London: Printed for E. Newbery, corner of St. Paul's Church-Yard.

pp. 51-4, Chapter 8, 'Washing the Lions'

I DREW this Picture from a real scene, of which I was an eye-witness. I made this sketch of it, not from any pleasure I received on seeing it, but as an admonition for the rest of my school-fellows, that they may be on their guard how they hastily give credit to the pretensions of designing people, who, while they seem to study our amusement, and excite our curiosity, are only contriving how they may make themselves merry at our expense.

It happened that I paid a visit to one of my friends in the Tower of London upon the first of April last; a day set apart from the rest of the whole year, in which the giddy and unthinking seem to claim a right of shewing their wit on those, who may not be so wise as themselves. While we were walking on the wharf, a harmless and inoffensive looking countryman came to the stairs, and asked some of the watermen, how long it would be before the lions were washed. The hint was immediately taken, and they demanded a shilling, on condition of their shewing them to him directly. The money was paid, he got into the boat, when that and two others went out a little way from the shore. Then crying out, Wash the lion, they began splashing him with their oars in such a manner, that he had not a dry thread about him, to the no small satisfaction of his pretended friends then on the wharf, and a great number of spectators, from whom, on his landing, he received no other consolation, than that they hoped he would remember being made an April-fool. The consequence of all this was, that the innocent caught such a cold, as had like to have cost him his life, besides being some weeks confined to his bed.

To this, our usher tells me I should add the following reflections: Young people should never indulge themselves in those diversions,which may prove detrimental to others and that it is a mark of the greatest meanness to take advantage of those who may not have had the same opportunity of improving their knowledge, as we may perhaps have had. It is the greatest pleasure imaginable to people of exalted minds, to instruct the ignorant, and rectify their errors, as they thereby acquire far greater honour, and more self-satisfaction, than they possibly can from exposing them.

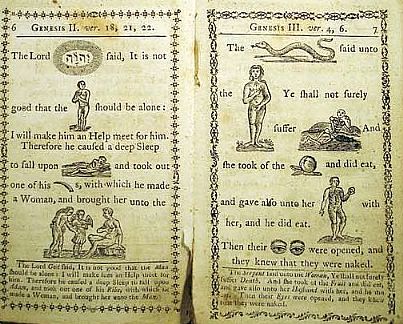

Another volume which is sadly incomplete, but which was no doubt well-loved, is a copy of the Curious Hieroglyphick Bible, 'with emblematical figures (wood-cuts) for the amusement of youth.'

The first hieroglyphic bible for children was published in Augsburg in 1687.¹ The form, in which a written word is simply replaced by its visual representation, proved very popular in Germany, but the first English edition did not appear until 1780. Published in London by Thomas Hodgson, it was reprinted in at least 20 editions before 1812; the first few editions are extremely rare, the first exceptionally so. These editions had woodcuts by Thomas Bewick, as does our copy. More editions from other publishers were issued later and the format and illustrations were sold to American publishers. The Priaulx Library copy has no covers and no title page but is very close to the 13th edition of 1796, which was published by Bassam after the death of Hodgson. The arrangement of pages differs between editions; another copy of the same 13th edition, however, has a different arrangement of pages again. Perhaps the publisher simply added a new title page to some old stock.

The 'hieroglyph' had been viewed as an aid to the teaching of reading, but gradually the rebus overtook the hieroglyph as the puzzle of choice and these bibles and other similar exercises lost their popularity.

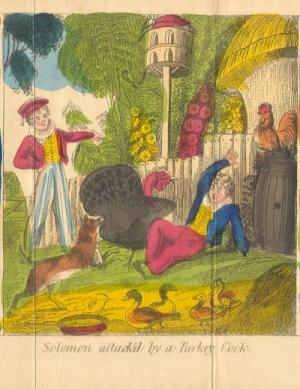

Fairburn’s Cabinet, or Fairburn's cabinet of instruction and amusement: containing the histories of Soloman Serious and his dog Pompey: Master and Miss Gracemore : Master Peter Primrose: Master Bentley: Amanda, or Virtue rewarded: The life of Mr. Thomas Thoroughgood: Helim, an Eastern tale: The basket maker: and The hermit: embellished with coloured engravings. This book was printed and published by J Fairburn, 110 Minories, London, between 1819 and 1842.

John Fairburn moved his print and chart shop from 146 Minories to number 110 in 1820. It is possible that the three-piece concertina illustration is by his protegé George Cruikshank, although quite hastily drawn. The illustration differs greatly from the those in the online Internet Archive; there are differences too in the list of books from the same publisher at the end of the volume.

Drawings include work for Johnny Fairburn, 'a jovial print dealer. Easygoing and good-natured, [who] became one of George and Robert's staunchest patrons. He was generous, too. It is said that when the Cruikshanks wanted money, they would place an empty purse marked 'unfurnished' on the mantel, and when Fairburn walked in, he would replenish it, as he frequently did for over the next quarter century' (Patten, George Cruickshank's Life, Times, and Art, p. 45).

John Fairburn was the publisher of the print The Capture of the Santa Brigada, a copy of which is in the Priaulx Collection.

Mince Pies is a little volume written especially for Christmas and dedicated on December 25, 1804, to:

MISS ELIZA PHILLIPS, A Young Lady, who, on this day, completed her 7th Year, With Wit and Beauty sufficient for Seventeen,

by her father, the author Sir Richard Phillips.

N.B. The Editor, as a suitable Encouragement to his young Readers to exert their Skill in solving the Enigmas and Problems in this Work, recommends that the Mince Pies, in all regular Families, shall be divided in the Proportion fo the Number of Solutions made by the several Candidates.

"MINCE PIES for Christmas! And dished up in the disguise of Riddles, Charades, and Rebuses! - What a trick!" will mammy's pampered darling exclaim, "I expected to have found something that was pleasant to my palate, and not a mess of things to puzzle my brains."

Sir Richard Phillips (1767-1840) was the self-educated publisher and editor of The Monthly Magazine. Said to have been born Philip Richard in Leicester, he was a schoolmaster, hosier, stationer, bookseller, vendor of patent medicines and newspaper proprietor in his native city, before arriving in London in 1795, where he set himself up as a bookseller. He eventually became Sheriff in 1807 and was knighted the next year, retiring to Brighton in 1823.²

.jpg)

Another unusual volume is Pussy's Road to Ruin, or Do as You are Bid, translated freely from the German by Madame de Chatelain, 5th Edition. This is undated but was probably produced around 1860. The publishers are given as William Englemann of Leipzig, Joseph, Myers and Co., 144 Leadenhall Street, and William Tegg and Co., 85, Queen Street, Cheapside. It has, however, an optician's label in the inside front cover: Carpenter and Westley, 24, Regent Street, London; this book was adapted as an extremely popular set of magic lantern slides. The illustrations are quite bloodthirsty and were no doubt highly entertaining. The author Clara (de Pontigny) de Chatelain (1807-1876) was a Frenchwoman residing in England, who wrote and translated many children's books under her own name and pseudonyms, and who was married to the Chevalier de Chatelain, a journalist well known for translating the works of Shakespeare into French.

Tales of the Castle, or Stories of Instruction and Delight, by Madm de Genlis. Translated by Thomas Holcroft, 2 Vols, London, Walker and Edwards, Paternoster Row, 1816.Frontispieces by Thomas Unwins (1782-1857)

This book and its author were very influential in the second half of the 18th century. Madame Stéphanie de Genlis (1746-1830) was a disciple of Rousseau (with whose ideas she did not, however, always agree) and an educationalist; her life was full of incident. She was a very accomplished harpist who is credited with repopularizing the instrument. She married the Marquis de Genlis but became mistress of the Duc de Chartres and (very unusually, as she was a woman) tutor to his son Louis-Philippe (1773-1850), who was to become the last King of France.

Mary Wollstencraft was not convinced:

Madame de Genlis has written several entertaining books for children, and her Letters on Education afford many useful hints, that sensible parents will certainly avail themselves of; but her views are narrow, and her prejudices as unreasonable as strong.I shall pass over her vehement argument in favour of the eternity of future punishments, because I blush to think that a human being should ever argue vehemently in such a cause, and only make a few remarks on her absurd manner of making parental authority supplant reason.For everywhere does she inculcate not only blind submission to parents; but to the opinion of the world -- With the same view she represents an accomplished young woman, as ready to marry any body that her mamma pleased to recommend: and, as actually marrying the young man of her own choice, without feeling any emotions of passion, because that a well-educated girl had not time to be in love.Is it possible to have much respect for a system of education that thus insults reason and nature? The Vindications, Rights of Women, Sect. 4

Jane Austen, however, was very interested in the works of Madame de Genlis, mentions her work and explored the themes of her writings in her novels (she admired Tales of the Castle, although some parts she thought 'indelicately' written). The book, known originally as Les Veillées du Château, was published in France in 1784 and translated by Thomas Holcroft. Holcroft (1745-1809) was a radical dramatist and writer who had spent time in Paris. He was the son of a London shoemaker who fell on hard times. A great friend of William Godwin, he sympathised with the revolutionaries in France and later was remanded but discharged without trial in England for high treason. Curiously enough, Madame de Genlis, whose work he translated and with whom he corresponded,had to flee France to escape the Terror, arriving in England in 1791; this was less to do with her ideas and more with her association with the Duc de Chartres; her husband was guillotined, and her son-in-law, Lord Fitzgerald (who was married to her illegitimate, secret daughter by the Duke), was killed by Irish rebels. John Walker was a wholesale bookseller who published other work by Holcroft.

Original Tales from my Landlord is one of a series of books illustrated by George Cruikshank and written by William Gardiner.³

William Gardiner was born at Whitchurch, in Herefordshire, April 16, 1766, and educated at Bristol under the celebrated mathematician Mr. Donne. In 1793, soon after his marriage, he left England for Philadelphia, where for two years he engaged in commercial pursuits. In 1796, he embarked a second time for America, and settled at Baltimore as a schoolmaster, where he remained till the spring of 1803. In 1804, he removed to Lydney, where he conducted a boarding-school. In 1817, he was introduced to Mr. D. Mackay, of Newgate Street, who engaged him to write some works of fiction, and as editor of The British Lady's Magazine. He died on May 18, 1825. A list of his numerous pieces will be found in The Narrative of his Life, by his daughter.4

William Gardiner's efforts to amuse and instruct children were not always appreciated; he was accused of bad grammar and plagiarism amongst other things. The titles of the stories in our volume sound exciting: The Force of Example, shewn by the history of Rajispund, son of the wise Scindy, vizier to the Sultan of Ava; and the vision of Cusco, an hermit of the Andes: The Royal Hungarian captives: The Silver Arrow: Maternal Solicitude, exemplified in the history of Prince Hippoocoo, the Dwarf Sultan of Delhi: The Dispensations of Providence, exemplified by the History of Congo, the black slave of Hispaniola, but,

His illustrations for Gardiner's oeuvre were re-used from one little volume to another, for each volume consisted of a number of separate stories, and the possibilities of permutation were endless. If the illustrations really are, as the title-pages claim, by Cruikshank, they are quite uninspired. Indeed, there is little in Gardiner's tales to inspire. Although they are dressed up in Oriental trappings, so as to fascinate the juvenile mind, and although they are granted the additional allurement of illustrations, their clear aim is to convince the child that he must suppress his imagination.5

1 Bookmen’s Bedlam, 1969, Walter Hart Blumenthal pp. 228-9

2 Mince pies for Christmas: consisting of riddles, charades, rebuses, transpositions and queries: intended to gratify the mental taste, and to exercise the ingenuity of sensible masters and misses: by An old friend. Printed for Tabart and Co., 1805 ([London]: T. Gillet); see Notes and Queries by William White, Vol 12, Jul-Dec 1855, p. 146

3 1825: printed and published by Thomas Richardson in Derby and sold by Hurst Chance and Company, London. This last story, Congo, is most interesting as it is highly sympathetic to its eponymous hero and very critical of contemporary American attitudes, which perhaps reflected the author's time spent in Baltimore, where, indeed, part of the story is set.

4 William White, Notes and Queries, Vol 12, Jul-Dec 1855, p. 146.

5 Robert L. Patten, ed., George Cruikshank, Princeton University Press, 1992, p. 97