An Eternal Stranger: Harman Blennerhasset

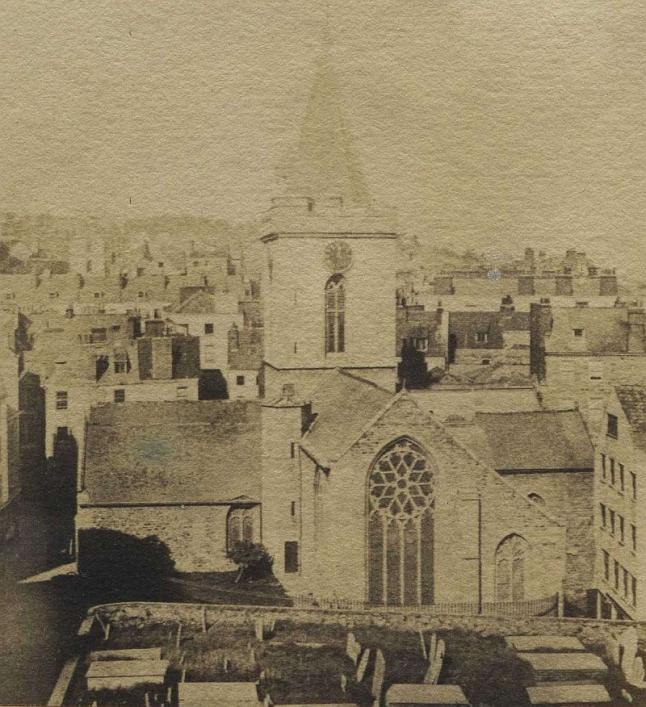

'Like mournful echo from the silent tomb, That pines away upon the midnight air, Whilst the pale moon breaks out with fitful gloom, Fond memory turns, with sad but welcome care, To scenes of desolation and despair, Once bright with all that beauty could bestow, That peace could shed, or youthful fancy know.' From The Deserted Isle, by Margaret Blennerhassett. Harman Blennerhassett was a clever but eccentric Irish republican who 'married' his niece, became involved in an abortive but notorious plot to make Texas independent, and ended up buried in Guernsey. The photograph above is from the Library Collection and shows the Cimitière des Soeurs, or Sisters' Cemetery, in 1870. The modern photographs in the article are of the Strangers' Cemetery as it is today.

In 1780 the Constables and clergy of St Peter Port were becoming increasingly concerned about the lack of space for burials in the Town parish. The population was increasing but the two existing cemeteries, the Cimitière des Soeurs1 next to the Town Church and the Cimitière des Frères, on the present St Julian’s Avenue, were tiny and plots had to be constantly recycled; the smell from the Town Church vaults, once the preferred resting place of Town grandees, was beginning to become overpowering. They mooted the idea of a new cemetery, where those who were poor or who were not of the Parish could be laid to rest. Thus the Cimitière des Étrangers, or Strangers' Cemetery, was created on steep land bought from the Reverend William Dobrée, next door to Elizabeth College, and bordered to the east by the Ruette Meurtrière, a muddy and sometimes impassable road.2

'Strangers' in Guernsey were those not born in the island. Although they could own property in the island, this conferred no automatic rights upon them. Pressure to build the cemetery is also thought to have come from the military, who required a place to bury soldiers from the garrison. After fifty years the Cemetery was superseded by Candie Cemetery next door, a considerably grander and neater affair which was planned over some length of time with a great deal of argument, and was based on the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris.3 The paupers of the Parish tended to end up in the Strangers’ Cemetery, nevertheless; burials continued to take place there until the 1880s, as Candie Cemetery, although ostensibly belonging to the parishioners of St Peter Port, was priced out of the reach of many of them. Even at Candie, plots bought in perpetuity were much sought after, and bodies were sometimes removed and reburied in these better plots, as people were well aware that bones were seldom left in peace in St Peter Port’s restricted cemeteries.

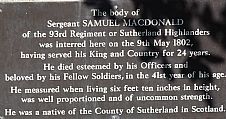

In 1807 the Ruette Meurtrière had been closed and Upland Road built through the middle of the Strangers' Cemetery, and the cemetery was divided into eastern and western sides. The road was widened in 1830, and those whose bodies had been disturbed in this process given new plots at Candie. In 1913 a cull was made of the gravestones, to The Star's disgust. In 1928 the Church handed responsibility for the Cemetery to the Town Constables, as no burials had taken place there for 50 years. In 1933, Spencer Carey Curtis transcribed the inscriptions on the remaining 500 or so stones. The eastern side of the cemetery was cleared and levelled, leaving only the stone of the giant 'Big Sam' McDonald, whose gravestone had been regularly maintained and who is still commemorated there. The stones were stacked up against the western wall.

Amongst the inscriptions catalogued by Carey-Curtis was this:

To the Memory of HARMAN BLENNERHASSET Esq., LL.B., and Barrister of the Hon. Society of the King’s Inns, Dublin, who departed this life Feb. 2nd 1831, aged 67 years.

The simplicity of the inscription belies the strange and exotic life of an Irish aristocrat, whose republican tendencies and extremely bad judgment led to exile from his adopted home in America and disgrace; whether this was justified or not seems open to debate.

The life of Harman Blennerhasset and his genealogy have been recounted in great detail by Bill Jehan in his comprehensive one-name study of the Blennerhasset family. Harman was born in Conway Castle, Killorglin, to a family of wealthy aristocrats originally from County Durham. His mother was Elizabeth Lacy,4 his father Conway Blennerhassett. He was named for his paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Harman. Educated at Westminster, he qualified as a barrister in Dublin. His sister Catherine married Major Robert Agnew, Captain of the garrison in the Isle of Man, and son of Brigadier Agnew killed at the Battle of Germantown during the War of Independence; they had a daughter, Margaret, a girl of some brilliance. In 1795/6, when Harman was 36, he married his neice Margaret, then aged 17; the marriage was not only clandestine (no trace of it can as yet be found) but illegal – if it took place at all. The families were horrified; Margaret seems to have been disinherited. Harman was also courting trouble by his active support for republicanism, to which he had apparently been converted while touring Europe. He and Margaret fled to America. Harman sold the Killorglin estate he had inherited and used the proceeds to acquire a library and the other accoutrements of a philosopher and scholar, which he shipped out to America with him.

After considering the advice of the Philadelphia élite for several months, especially that of a new friend, the banker Joseph Lewis, the couple travelled to Ohio, then the 'frontier', and purchased the upper part of an island in the Ohio River below Parkersburg, West Virginia, near Marietta, Ohio, from a local newspaper editor, Elijah Backus. Where there had previously been an Indian rendezvous the Blennerhassetts built a huge mansion and lavished money on the finest furniture and magnificent gardens. They invited all the highest society to visit and dine with them, and the beauty and magnificence of the house and Blennerhassett island became celebrated. They had chosen a state which slave-owning was still legal, though it had been outlawed only a few miles away in Ohio, and housed twenty or so slaves on the island in a separate building.

They had several children, adopting first in 1798 the eight-year-old son of a French doctor, the grandson of Elijah Backus; their eldest son Dominick, (b. 1800), an alcoholic 'degenerate', disappeared at 28 and second son (b. 1803) Harman Jr., though at first a lawyer in New York, became an invalid and, although looked after by his mother, died in a poorhouse after her death; Margaret Jr. died aged two in 1803 and is buried on the island, as is their six-year old other daughter. Their youngest son, Joseph Lewis Blennerhasset (1812-1862), survived to become a lawyer and teacher, and an accomplished scholar.

In modern times, Margaret Blennerhasset and her poetry have begun to interest historians more than her husband. Her personal qualities, looks, and acute intelligence, and the beauty of the 'island Eden' she had created played a large part in saving her husband from jail after he became embroiled in 1807 in the separatist plans of the charismatic vice-president, Aaron Burr, whose secret conspiracy he helped to bankroll. Harman, who had previously spent his time on the island quietly, conducting experiments, hunting, and philosophising, has often been portrayed as a dupe, but Margaret was very ambitious, the couple overspent, and Harman was certainly a fervent republican. The couple had already more than determinedly defied convention and the law in getting married at all, Harman’s wealth allowing them to create their own private world where the rules were their own; perhaps they were simply naive fantasists. It was Harman who innocently revealed details of the plot to an undercover spy. The Blennerhassetts were ruined financially – the failure of the plot perhaps tipping them over the edge – and Harman was popularly thought of as a traitor, although found not guilty at his trial.

The house on Blennerhasset Island, from which the separatist expedition was intended to sail, was severely damaged by the Virginia militia when the Burr Conspiracy was discovered. Harman and his family tried to regain his wealth and in 1807 bought a cotton plantation in what is now Missouri, which they called 'La Cache', where they built a smaller version of their famous house; this house was accidentally burnt down in 1811 by the slaves of a tenant farmer and the island was bought in 1817 by their old friend, Joseph Lewis. The plantation, bought just before the collapse of the cotton market, was not successful. After spending time working as a lawyer in Montreal, Harman returned to Ireland in 1822 to pursue a futile claim in the courts. From there he moved to stay with his unmarried sister, Avice Blennerhassett (1743-1838) in Bath. In 1826 the whole family moved to St Aubin in Jersey.5 At this time the Channel Islands with their low rates of tax were considered an ideal place to retire, and the climate beneficial to those in poor health. Two years later they became tenants at 1, Mount Row, St Peter Port. Their son, Joseph Lewis, stayed in Jersey where he qualified as an advocate. After teaching in Ireland and Wales he eventually returned to the United States, to help his mother pursue a claim against the government, where he practised law and taught.

In February 1831 Harman Blennerhassett died. In his will6 he specifies that his funerary expenses should be strictly limited 'to no greater on the instant than those of an ordinary Labouring man. And therefore that my Body may be interred in the Night Time.' T. F. Priaulx, in a short note about Blennerhassett in the Quarterly Review of the Guernsey Society (Autumn 1961) XVII (3), p. 49, makes the following (unsourced) observation:

No. 1 is on the Mount Row—Prince Albert's Road corner and has a pillar box set in its front garden wall. With the Blennerhassetts lived his sister Avice, his mistress Mrs Mary Nelburn, a milliner in St Peter Port, and her child—probably his too—also named Avice. He had practically nothing left but Mrs Nelburn had some money and she kept them all. .... He appointed Mrs Nelburn executrix of his Will and expressed his warm appreciation for her financial generosity, he also expressed the hope that the three women—his wife, sister, and mistress—would continue to live together and he shared his few possessions between them. .... what became of the others and the child Avice is not known.

In fact, Bill Jehan provides this information7 from Candie Cemetery; the Nelburns and his sister were all dead by 1849. He also quotes a book of 1939 which gives an extended version of Harman Blennerhassett's memorial inscription:

He passed through a variety of changes during his active life. Nearly thirty years of which he passed in the U.S.A. & Canada. While in America at one time he owned a most beautiful Island in the Ohio River which still bears his name. He was a man of (...) true piety to his Creator, philanthropy and virtue, and was possessed of great acquired and natural ability and talents. He departed this life on the 2nd February A.D. 31 in the 63rd [sic] year of his age. His bereaved wife and son caused this monument to be erected to his memory ... Strangers pass not by without dropping a tear.

If this memorial stone ever existed it had gone by 1933. In 19588 the Constables cleared the site, and in the 1970s the eastern side was used to build a bank, forming the front garden and car park, and later a new gymnasium for Elizabeth College. 2,000 bodies were exhumed and reburied in the Foulon cemetery, and amongst these may have been Harman Blennerhassett. If he was not moved then, his body still rests in the remaining part of the cemetery, along with perhaps 3,000 others, under grass and trees. His magnificent house on Blennerhassett Island, however, was completely rebuilt in 1982 and is now a West Virginia State Park, rekindling an interest in Harman and Margaret’s lives. Margaret and her son Harman Jr. were buried in the New York vault of their Irish nationalist family friend, Robert Emmet, but were recently brought back to Blennerhassett Island and re-interred next to her daughters.

1 By 1811 the problems had not been solved: the Gazette de Guernesey of 10 August, 1811, (p. 127) features a poem in English, written four days earlier following the author's 'visiting the Parish Church-Yard,' in its present awful state:

Here where the dead in hopeful rest should sleep,

Their rude confusion marks a mingled heap;

Half-dropping skulls, that ask a gasp of breath,

And seem to cry 'Respect the sons of Death;'

Robb'd of their home, their tenement of clay,

No more we trace where once our Fathers lay;

Whilst mouldering bones on ev'ry side appear,' &c.

The author is outraged: 'I, a few days since, accidentally entered the Church-Yard, and could not but be shocked at the indignity committed against the dead, when I beheld their once-hallowed dust, brutally thrown over that wall which secures this sacred repository from the encroachments of the Ocean.' See also newspaper reports of March 1820. The neglect and overcrowding continued for decades: A.C. Andros, 'The Guernsey Golgotha,' a letter complaining about just the same thing, from the Star, Sept. 23, 1884, in Reminiscences II p. 162. In 1929 it was decided that the cemetery should become an amenity; the stonemason E. Henry, of the Bordage, took it upon himself to transcribe the stones that remained. A list was published in the Star newspaper of which a copy can be found in the Sisters' cemetery file in the Library; it includes some interesting people.

2 See A Short History of the Strangers' Cemetery by Gillian Lenfestey. All information on the Strangers' Cemetery, including lists of surnames, is held in a file at the Library. In his history attached to the list of memorials, Carey Curtis explains 'the Ruette Meutrière was the name of a Lane, which in old times, led down from what is now the Grange, then called the Castel Road, at the back of the Elizabeth College grounds to what is now called the Rue des Frères and Hospital Lane.'

Going up to the Grange-street for the dozenth time, to look at the superb aloe, which is just at the corner by the College-wall, I sauntered down a road leading to the New Ground. The wall on the left incloses the burying ground. Conspicuous among the tombs is that of a Chevalier, emigré, who must needs write his own epitaph in very limping French verse, saying something about his having found an asylum here for his persecuted loyalty. The strain of panegyric on himself, aided by the hobbling poetry in rhyme, struck me, instead of being impressive, as supremely ridiculous. [From The United Service Magazine, 1838.]

3 Nicola Tyson, 'Candie Cemetery and its Monuments', Transactions of the Société Guernésiaise XXIII (3) 1994, p. 599.

4 Elizabeth was the daughter of Major Thomas Lacy of the 33rd Foot. He and his daughter Katherine Pool are commemorated in Winchester Cathedral; Harman himself was born in Hambledon, Hants, near Winchester, while his parents were visiting family.

5 There are other connections with Jersey: Margaret’s neice Mary Eleanor Agnew (1809-1880) married a Jerseyman, Lyndon Philip Poingdestre, in Jersey in 1834 and emigrated from there in 1848, settling in Australia.

6 Proved in Guernsey; a copy is in the Library.

7 Avice Blennerhassett, d.7.2.1838 at Guernsey, bur.15.2.1838 Candie Cemetery, St.Peter Port, plot D77X; with Avice Nelburn bur.2.4.1834 & Mary Kimber Nelburn bur.29.4.1849. The memorial inscription is from Lowther, Minnie Kendall, Blennerhassett Island in Romance and Tragedy, with the Burr Episode entwined about it: Rutland, Vermont, Turtle Publishing Company, Vermont, 1939. Mrs Nelbern came to Guernsey from London in February 1828, residing first at 323 Fountain Street, opposite the Fish Market 'where she has commenced business in the stay-making line' (See the Star, February 26th, 1828.]

8 A couple of stones resurfaced in 1974, having been reused at the pet cemetery at the Animal Shelter before the Second War and bulldozed over by the occupying forces. For the activity of 1913, when memorials to the dead were 'ruthlessly removed from the heads of the graves, and as unceremoniously stacked against the [west] wall or else piled on top of the other,' thanks go to David Kreckeler for drawing attention to The Star of October 30 and December 24, 1913. Twenty elm trees were planted at the Cemetery at the same time to replace those blown down in a gale.

For the legal status of Strangers, see Bails and rents.

Other items of interest:

Safford, William H., The Life of Harman Blennerhassett, 1850

Blennerhassett papers; Blennerhassett papers in Virginia Libraries

A resume of Harman Blennerhassett's life

Outhwaite, R. B., Clandestine marriage in England 1500-1850, Rio Grande, Ohio: The Hambledon Press, 1995: available at the Library