Autobiography of Thomas Fiott De Havilland, engineer and architect

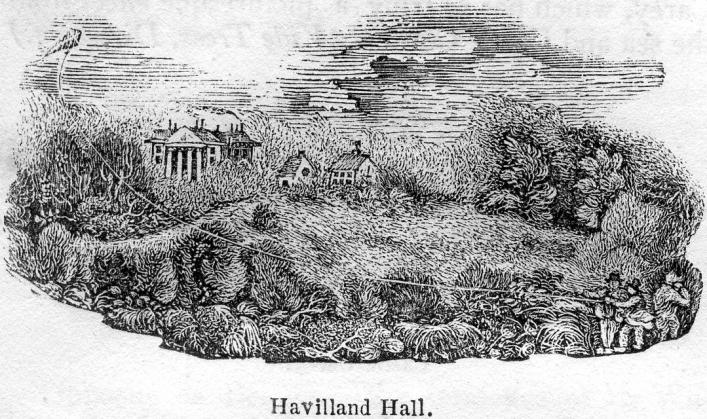

Builder of the now lost 'De Havilland's Bulwark', St George's Cathedral, St Andrew's Kirk and many other buildings at Madras, now Chennai, and here in Guernsey, Havilland Hall. From his book, The De Havillands of Guernsey, published in 1854. He died in 1866. The woodcut is by Dr Thomas Bellamy from his Pictorial Directory of 1843, in the Library collection.

The foregoing notices refer to the construction of this little work, and may serve to revise it [....] They will, of course, mostly concern myself; my own immediate descendants may be but few, having survived my only two sons, Thomas and Charles Ross, who, between them, have left only one child, my posthumous grandson, John Thomas Ross, (son of Charles Ross, and of Grace Dorothea Verner, his surviving widow), still very young and weakly! But the Lord's will be done!

I was born in St Peter-Port, Guernsey, on the 10th of April 1775. In 1791, a Madras Cadetcy was obtained for me, and, leaving England on the the 7th April, 1792, I reached my destination on the 1st August of the same year. In those days no educational establishment was extant, for preparing and qualifying cadets, as at present; they then all arrived in India, unprepared or uneducated, as might be, but unappointed to any particular arm of the service; to be subsequently chosen and posted to corps by the local authorities of their Presidency. So accordingly, in 1793, I was posted to the Engineer Corps, and rose regularly in that line to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, to which I was promoted in 1824, and in this grade, when the senior officer of the corps was not present, I had occasionally to perform the duties of Acting Chief Engineer. I left India, finally, in 1822, and retired from active service on the 20th April 1825, having then completed the fiftieth year of my age, and the thirty-fourth of my services, from the time of my appointment at East India House; but I had, in the interim, twice visited my native land, namely, in 1802-3, and in 1810. My retirement from the service was on the pay of Major only, not having returned to India after my last promotion.

I may here, by the way, remark, that although I was employed on all occasions, (or at least, volunteered so to be,) as against Pondicherry, in 1794, against Seringapatam, in 1798-9, on Ceylon, in 1796-7, and in Egypt, in 1801-2; I was apparently fated to see but little, and no severe, active military service. I should say, however, as regarding the expedition to Egypt, that on the late Duke of Wellington being appointed to command it, he personally applied to the Governor of Madras for my services on that occasion; and on my joining him, he appointed me Field Engineer to the expedition, with a handsome remunerative salary! I had left two staff appointments, in India, to join him; but he was subsequently superseded in the command by General Sir David Baird, the former having been reserved by his brother, the Marquis of Wellesley, then Governor-General of India, for the Maloratta campaign; in which he eventually reaped his first laurels; at Assye, Argaum, and Gawilghur, in 1803.

The expedition to Egypt arrived at its destination too late for the object Government had in view, in ordering it, through the Home authorities; nevertheless, Sir David Baird, then commanding it, detained me in that country upwards of a year. I there first joined the Royal Engineers, under the command of Sir Alexander Bryce, and was employed by him on a survey of the Lake Mareotis, near Alexandria, for a copy of which survey the Honourable Court of Directors were subsequently pleased to present me with a purse of one hundred guineas!

Afterwards, when Sir David Baird contemplated returning with his troops to India, he directed me, with a company of pioneers at my disposal, to visit, examine and report upon the desert from Cairo to Suez, and, if possible, by digging for it or otherwise, to discover and supply water for the India troops, which, with himself, were to return by that route; and having been entirely successful on that service, I received the general's thanks, with permission to take my furlough to Europe, which (having very nearly served the ten years required by the rules of the service,) he considered himself authorized to grant; then, sailing from Alexandria to Malta, and thence travelling overland, I reached Guernsey on the 9th January, 1803.

I soon returned to India, by the Admiral Aplin, Captain Rogers; but, after crossing the equator the second time, we were taken by the French privateer, La Psyché, near Hog Island, off Sumatra. The Aplin defended herself nobly till she had had two military officers, passengers, mortally wounded. The disparity of force between the combatants was awful, the Psyché had been a corvette and had two captains of the French Navy, Trehouart and Rivière; who behaved most courteously to all their captives and respected private property; and took on board the privateer, Captain Rogers and some of his officers and passengers, of whom I was one, and by means of a neutral vessel we were ulteriorly landed at Calcutta; and thence I found my way to Madras, in the spring of 1804.

Shortly after, I joined a detachment of the Deckan force, under the command of Colonel Haliburton; and while there I made a sketch survey of the Berar, Candeish and neighbouring provinces, by a special order of the marquis of Wellesley, who was so well pleased with it, that, after approving of it in flattering terms, he applied to the Madras Government for my further services, to complete that survey! But I was required elsewhere, and could not then be spared. This was to carry out a thorough reform of the fortifications of Seringapatam, so as to make it a centrical stronghold in the peninsula; the plan had been prepared by the Chief Engineer, General Ross, then leaving India. The project, however, was abandoned by government; and I remained at that station as Superintending Engineer.

I was still there when the temporary quarrel of the Madras officers, with Sir George Barlow reached that garrison, and I was involved in it with the rest of the officers, although, as I now solemnly declare, unjustly implicated. [For the details see The court martial of Thomas Fiott De Havilland.] Thus restored, I returned to India, in April, 1814, with my family, and on arriving there was heartily greeted by my old friends and brother officers; by the Government also, and especially by the then governor, Mr Elliott, Lord Minto's brother; who courteously told me, when referring to past events, 'All that now belongs to ancient history; and Government must find a situation to suit you, so as to avail itself of your talents and abilities!' I now joined the army under the commander-in-chief, (then encamped for field service,) as his Field Engineer. But, I found that of the many officers implicated in the late defection, only three remained unrestored to the service, and that their more fortunate brethren, had yet done nothing for their much desired relief; I then sat down to consider what had best be done for them, and prepared a programme of all the company's corps, with the sum I thought each might be willing to subscribe in such a cause, opposite to their Nos.! It amounted to £16,000; and rather more than that sum was eventually collected and distributed among the sufferers; all which was effected without opposition on the part of Government, although done in open day. This measure served as a salve to the wounded feelings of all parties, and abated the excitement raised throughout the country. The three unrestored officers were Lieutenant-Colonel Bell, commanding Seringapatam; and Captains McKintosh and Askill, who left Chittledroog, with their two battalions, for Seringapatam, without orders.

Sir Thomas Hislop's camp soon broke up, and from that time, till I finally left India in 1822, I was never unemployed; but it was chiefly in the civil department of my profession; frequently holding several of the following appointments at the same time, viz. first Engineer and Assessor to the Madras Justice; secondly, Superintendent of Tank Repairs; thirdly, Inspector-General of Tank Estimates; fourthly, Civil Architect at the Presidency; fifthly, Superintending Engineer of Fort St George; and sixthly, Acting Chief Engineer.

During the above period I constructed many works of importance with success, of which I shall only notice two; first, the Scotch National Church, or kirk, at Madras, dedicated to St Andrew; and secondly, the Madras bulwark. The first is accounted a handsome building, and is of peculiar construction, being entirely of masonry, (chiefly brick,) save only the door and windows of teakwood, and the pulpit and pews of mahogany; the latter divided by arms into single sittings, and all ranged concentrically to the pulpit; the pavement was marble, black and white, checkered.

The outline of this edifice is an oblong square, with a spacious portico at the west end, and a sort of chancel at the east. Over the centre of his edifice, a circular dome, fifty-one feet of interior diameter, rises and forms part of the roof; it rests on a stone entablature, placed on the capitals of sixteen pillars of the Ionic order, in a circle, supporting it; and the whole superstructure is firmly kept in equilibrium by an annular arch, leaning against the outer walls, and supporting the terrace round the dome, which completes the roof.

Between the portico and the dome is the belfry tower, surmounted by a handsome steeple, whose weather-cock is about one hundred and seventy feet above the surface of the ground. The whole masonry of this church is endued with excellent shell stucco, or cement, inside and out; and the interior of the dome is coloured, to represent the blue firmament. The whole cost of this kirk was about £20,000; a large portion of which sum was absorbed in the foundations, which are sunk on wells, some twenty or twenty-five feet deep, through a stratum of black salt mud, and some sand; a marine deposit, which seems to have been there for the untold centuries of an almost unimaginable period.

The foundation stone was laid with all due ceremony on the 6th April, 1818; and the work was competely finished within two years, to the satisfaction of Government and elders of that Church.

Respecting the Madras bulwark against the sea, I should premise that the Madras surf is known and generally acknowledged to be one of the most violent in the world; the sea is shallow for some distance out, and the ground swell occasioned thereby, when it arrives at the margin of the shore, breaks over irresistibly, and even in calm weather rises very considerably. The present work was carried along the sandy beach, skirting the Black Town and Fort St George, on a length of 10,800 feet; its main object was to protect the town, then considered in imminent peril, from the sea encroachments; but it was also to strengthen some of the fort out-works, besides arresting the corrosion and wearing away of the shore, by the continued currents along that coast, from the NE and SW alternately, according to the monsoon. This bulwark was built in a continuous and almost straight line, as shewn in the accompanying lithograph.

Some previous attempts to arrest this evil had failed of success; but I had so studied the action of the elements on that coast, even at other points to the southward, besides Madras, that I felt confident and ready to undertake another effort to obtain the desideratum, by securing the town and fort against disaster. I remembered that in 1792, the landing place was full a furlong from the fort, and a custom-house shed stood there, on the sand, for the convenience of goods and passengers at landing; this circumstance assisted my judgment, as to the rate at which the shore was being washed away by the currents, and as to the power necessary to check it; provided only I were myself allowed to plan and carry out my own project. Being at the time Superintending Engineer, I had to watch and officially report on the growing evil, and to suggest effectual measures to arrest its progress, which I did accordingly. My project was a very simple one, a mere glacis, seaward, of considerable dimensions, made of large blocks of stone, as they were brought from the quarries a dozen miles off; and laid on the beach carefully, after removing the sand to a sufficient depth to secure them, being backed by a good retaining wall of masonry. But there was to be no super-pavement applied; as, in my mind, a smooth ascent could only serve to launch over, with greater force, the waves and surfs coming upon it, at each rolling swell from the sea; to the prejudice of the very objects it was intended to protect.

My project was submitted to the Chief Engineer for his report, and for him to forward plans and estimates for the same; which were then sent me by Government, to carry out; but I found that wooden piles along the foot of my glacis had been introduced by the Chief Engineer, and as I had fully considered the subject and still deemed them quite unnecessary, nay, even of very doubtful advantage, I appealed to Government proposing to dispense with them; but the Government unwilling to decide the question on its own responsibility, replied, that I might do so, but on my own sole responsibility; and I accordingly did so, although at my own personal risk.

I now pushed on the work all I could, and in thirteen months I had gathered on the spot the mass of materials required, and had begun to lay the stones down. On the 19th July, 1822, Government reported the work finished to the Home Authorities; in that report Government described the work as being 'beyond all comparison the greatest and most arduous work ever executed by any individual under this Presidency!' and that my claim to remuneration, if estimated as it ought to be, by the difficulty of the undertaking, and the perseverance with which it had been brought to a conclusion, which it was believed had rarely, if ever, been equalled!

In the Military Board's report to Government, of the 28th December 1821, they, in strong terms, adverted to my services in planning and executing the work, to the talent I had displayed therein, and to my indefatigable zeal in completing the work in so superior a manner; they also declared that those circumstances entitled me to their warmest acknowledgments, and, in submitting my claims to the consideration of Government and the Court of Directors, they say, they are confident that my merits on that particular occasion would be duly estimated, and that I should be especially remunerated, in the most liberal manner, that either the rules of the service or cases of precedent, could with propriety admit of! that it should be at least 8 per cent on the estimated amount, or on the actual disbursement; in the former case it would have amounted to nearly £6,000, and in the latter, to upwards of £7,000. But Sir Thomas Munro, with all his praise and admiration of the work, and of my zeal therein, would only allow me £5,000, which he himself said he was persuaded was not a fourth part of my actual saving to the Government. He estimated that saving at more than £20,000! but it all availed me nothing, even although such saving had been, as aforementioned, effected at my own risk!

The year after I left India was remarkable for severe weather at Madras, and in allusion to that, the Court of Directors wrote thus to the local Government. (November, 1823). 'We have learned with much satisfaction that the Bulwark has stood the test of storms, since Major De Havilland's departure from India, and that all the advantages expected from it have therefore as yet been fully realized! But now upwards of thirty-one years have elapsed since the completion of that work, during which it has continued to be tested by many other storms; unaffected, so far as I can learn, by them; and I trust will long continue to protect that important strand of the Coromandel coast.

I may here mention some circumstances which evince the entire confidence which the Government placed in me, regarding this wiork. Public opinoin was ceratinly against me, and Government received many representations stating my project to be a mere vagary, unworthy of the least attention. Government referred all such documents to me, but was always satisfied with my reply to them, without further enquiry.And, again, it so happened that while carrying on the work, I became senior officer of Engineers at the Presidency; now, by the rules and practice of the Service, I was to become the Acting Chief Engineer, and another officer, mu junior, called dwon to take charge of the bulwark; nevertheless, Government, unwilling to trust it out of my own hands, appointed me Acting Chief Engineer, as matter of course; but I was at the same time directed to proceed on with the bulwark. This was indeed an unheard of anomaly, as officially I also became member of the Military Board, or Board Of Works; that Board, in their previous report, went on to say; Major De Havilland had undertaken the work as Superintending Engineer at the Presidency, and the Government having in their wisdom deemed it proper that this most important work should be continued under his immediate order, after succeeding to the office of Acting Chief Engineer; we may, we think, presume, that it was not the intention of your Excellency in Council to impose an extra duty of such magnitude, and where so great an extent of responsibility must be required, upon Major De Havilland, without the consideration, that eventually a corresponding remuneration would be required to be made to him.'

I accordingly took charge, did the duties of both offices, and drew allowances for both; moreover, I feel persuaded that Sir Thomas Munro was moved therein, entirely by the confidence he reposed in my thirty years' experience, and in my professional character; for I had no personal claims on him whatsoever.

So, likewise, in reference to the facts, that both the Marquis of Wellesley, when Governor General, and his brother, the Duke of Wellington, when commanding the Egyptian expedition, did each of them specially apply to the Madras Government for my services; the one in my civil capacity of Surveyor, the other, in my military calling of Field Engineer; I may assume that such applications were founded on the professional character I then bore; since I had not the honor of any personal claim on either of them.

After completing the Madras bulwark, I returned home with my family. Indeed, a year or two before, I had contemplated doing so, on sick certificate; but Sir Thomas Munro, having then possibly in view the construction of that great work, and finding my disorder not to be of a very serious nature, entreated me to postpone my departure, which I accordingly did. The return of Colonel Caldwell, from England, was then looked for, but he did not arrive until the bulwark was far advanced; and he then relieved me in the office of Acting Chief Engineer.

I may, in this place, say a few words respecting my marriages. My first was at Madras, on the 3rd September, 1808, to Elizabeth De Sausmarez, daughter of Thomas, Esquire, Seigneur de Sausmarez, de St Martin, à Guernesey; (he was the King's Procureur, or Attorney General, in that Islands,) and of Martha Dobrée, his wife. Our attachment dated from 1803, when I was in Guernsey; but circumstances preventing my return afterwards to marry, she came out to me, and we were united as aforesaid, at Madras. Alas! however, our union, though a most happy one, was of but short duration, for she died at Madras, and was buried there on the 14th of March, 1818. She was born on the 13th of October, 1782. Hers was the first body deposited in the new cemetery I was then constructing for St George's Church, now the Cathedral of the Madras diocese; she left me four children; the first Emilia Andros, unmarried; secondly, Thomas, a brave officer, who entered the army, and died on the 6th of September, 1843, a Captain of the 55th Foot, at Hong Kong, in China, of a typhus fever; where a monument was erected to him memory, by his brother officers. He had been magistrate at Chusan, and surveyor at Hong Kong, where he died, unmarried, and regretted by all who knew him. Thirdly, Elizabeth Martha, born in India, 26th of November, 1815, and married the 17th of June, 1841, St John Gore, Esq., son of the Reverend Thomas Gore, of Malranean, Ireland; they went off to Australia immediately, with all his family, where they still remain, but have no children.

Fourthly, the Reverend Charles Ross, MA, born in India, the 22nd of June, 1817; married in Guernsey, by the Bishop of Winchester, the 12th of August, 1843, Grace Anna Dorothea Verner, the daughter of David, Esq., and of Anna Wilford Cole, his wife; he died (and was buried at Merton, Oxfordshire) on the 6th of October, 1851, having lost two infants, who were buried in the same tomb with him, and leaving his widow pregnant.

Having returned from India, in 1823, I took up my residence in Guernsey, where in 1827, I purchased the small Vauxquiédor estate, and in 1829-30, built Havilland Hall upon it. In the meantime I had married, secondly, the 6th August, 1828, Harriet Gore, youngest daughter of Anthony, Esq., and of Judith Dobrée, his wife. She is still living, but has had no children.

I soon took an interest in the politics of the island, and was for six years the representative of St Andrew's parish, at the States, from the 9th April, 1836; and in 1842, I was elected, by a large majority, to the bench of the Queen's Court, in Guernsey, which I still attend, as Juré-Justicier, (vulgo), Jurat. Havilland Hall has been for ten or twelve years, and still is, the residence of Her Majesty's Lieutenant-Governor of the island, having let it to Government for that object.

Her I close my Biographical Notes, having on the 10th ultimo entered my eightieth year; and I dedicate them to my dear children, and grandchild, John Thomas Ross; and the Lord's name be praised, I am still enjoying excellent health, with unimpaired intellect.

In appearance Thomas de Havilland was short and slight. At the age of 20 he was just under 5 feet 6 inches in height, and nine stone in weight. He possessed a strong constitution and great physical and mental energy. He was intelligent and clever.

Elizabeth de Sausmarez (1782-1818), Mrs Thomas Fiott de Havilland. Daughter of Thomas de Sausmarez and his first wife, Martha Dobrée. She was known to her brothers and sisters as Betsy, but to her husband as Eliza. In 1797/98 she spent a year at school in England, and after leaving school spent a couple of months with her Uncle Rowley in Malling before returning home. As a young woman Elizabeth was, in the words of her step-mother, 'everything that a fond parent could wish, a fine, amiable, sensible girl.' She was attentive and kind and an excellent artist. Of her personal appearance we know little. She was taller than her great friend Nancy de Havilland, and had dark eyes. In the spring of 1803 she fell in love with Thomas de Havilland, who wanted to marry her and take her back with him to India. However both Thomas de Sausmarez and Peter de Havilland felt that Thomas did not yet have a sufficient income and decided that he should return alone, better his position and then come home to marry Elizabeth. Thomas had to agree. The engagement remained a secret. Thomas’ prospects were damaged by his capture on the way to India and he realised that it would be a long time before he could leave India for good. He pressed constantly for Elizabeth to be sent out to him and eventually in 1807 Thomas de Sausmarez relented. Elizabeth sailed for India on board the William Pitt in March 1808, and arrived at Madras at the end of August. She and Thomas were married at Madras on 3rd September. Elizabeth’s first child, a son, was born in August or September 1809. Elizabeth was seriously ill for several months after the birth, and the baby died on 24th October. In May Thomas resigned his commission and he and Elizabeth, who was again pregnant returned home. They arrived in September or early October and the child, a girl was born on 16th November and christened Emilia.Thomas and Elizabeth remained four years in Guernsey and set sail for India in May 1814, arriving at Madras in September. Their other children were: Thomas, born 31st May 1812 in Guernsey; John, born in Guernsey, October 1813, died 1814; Elizabeth, born in India 26th November 1815; Charles Ross, born in India 23rd June 1817. Elizabeth died in India on 14th March 1818. Thomas said the cause of death was an abscess of the liver. [Biographical notes from lemarechaldesaxe.]

See also the Comet, August 4th 1836 &c.

His Journal of the Ceylon campaign (Cambridge University.)

Archive of letters at Yale University (Thomas Fiott De Havilland Correspondence, 1799-1844. James Marshall and Marie-Louise Osborn Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.)

Letters from the Madras presidency (Bonhams).