Basket-lifting in 1833: the perils of having nothing better to do

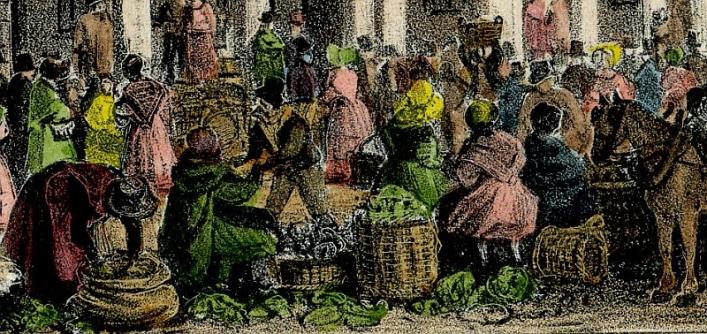

The Comet, Friday, November 8, 1833. The illustration is a detail from a contemporary 'Moss' print of the Guernsey Markets.

We are informed from a highly respectable source that basket-lifting is carried on to a much greater extent in our public markets than most persons seem to be aware; and it has been suggested to us that, in all probability, the evil in question has its origin with a number of idle fellows who are employed as errand boys, who may be seen sauntering about the markets, watching the opportunity, when persons are busily engaged in making their purchases, to seize upon their prey. Boys of that description should not be encouraged; for whilst they pick up a trifle by carrying meat or fish, it affords them an opportunity of making their observations on the state of Ladies’ reticules, or the baskets carried by servants, and when a favourable moment presents itself for their purpose, they reduce it to practice by degrading acts of pilfering, and thereby acquire a vile propensity dangerous to society, and ruinous to themselves.

There is no condition so fraught with mischievous consequences as that of idleness. Boys who are not brought up to regular habits of industry in early life, seldom make useful members of society. Their indolent courses puts it out of their power to obtain a livelihood by legal means, and in order to supply the cravings of nature, they have recourse to wicked practices which too frequently lead them to an ignominious and disgraceful end. Hence arises the necessity of discountenancing idleness in every possible way, for by so doing the incentive to malpractice is disarmed of one of its most potent instruments of mischief. If the characters in question were employed in learning some useful mechanical art, they would in the first place be removed from the scene of temptation; and in the second place, a foundation would be laid for their usefulness in later life; but because this is too much neglected, it is no wonder that these hapless youths become vagrants at a very early period of their existence, and finally become the terror of the community in which they live. Closely allied to idleness is drunkenness, and, if we mistake not, the latter is a natural consequence of the former; so we see that those who are addicted to such an evil appear to be fit recipients for an unnumbered train of other evils, which are disgraceful to human nature, and utterly subversive of all order, decency, and propriety.

Before we quit this subject, we would observe, that if parents cannot find immediate employment for their offspring, they should, to keep them out of harm’s way, see to it that they are sent to school on proper time, and by no means be suffered to saunter about to the injury of their morals, and the neglect of their education. Poverty need not be pleaded as an excuse on this score, for public benevolence has provided that every man and woman should be left without excuse on this ground, so far as it regards his, or her, children. There are public schools, be it said, to the credit of our country, in which the children of the poor may be properly educated and fitted for the respective stations they are designed to fill in the world, so that if they remain ignorant of their duty to God and man, it is utterly their own fault.