Eliza Cook's Trip to Sark

30th May 2025

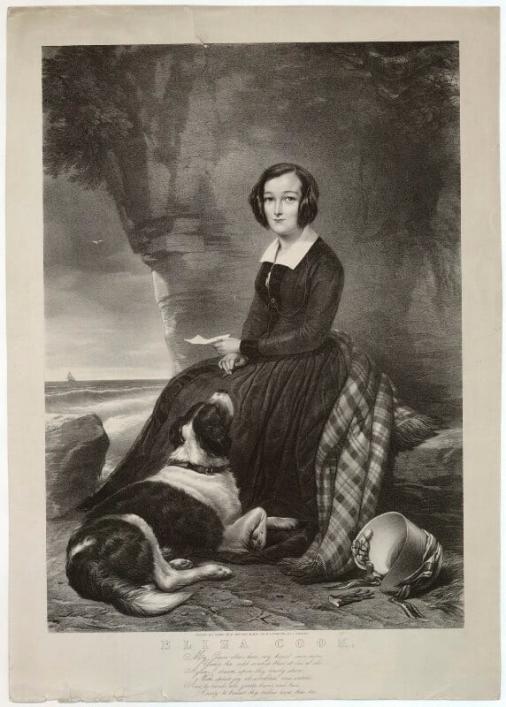

From Eliza Cook's Journal, Saturday, August 19, 1854. Eliza Cook was born in Southwark in 1818 as one of eleven children to a tinsmith. She began her career in poetry at a very young age, and had much success, her poems being published in newspapers and proving especially popular as songs when set to music. She was a Chartist, and her poems often deal with the "levelling-up" of the poor. From 1849-1854 she wrote, edited and published Eliza Cook's Journal for, she said, 'utility and amusement'. Despite her popularity, she is now largely overlooked. The portrait is by Henry Brittan Willis, after John Watkins:

lithograph, 1840s-1850s, (c) National Portrait Gallery, NPG D34087

A TRIP TO SARK.

ONE fine afternoon towards the end of July, 1851, we embarked in the Guernsey roadstead, on board the Native, a small cutter, plying between the two islands, and fulfilling the double mission of packet-boat and trader.

We had heard so much concerning the grandeur of the Sark scenery—had, moreover, during our stay in Guernsey so frequently admired its bold line of coast, that we determined on seeing with our own eyes these hidden treasures before leaving the Channel Islands.

Having weighed anchor, we rapidly passed Castle Cornet, a middle-age fortress, which completely commands the entrance to St. Peter's Port, and proved almost impregnable to the Parliamentary force during the civil After this the only objects of interest are the islets of Herm and Jethou, lying about midway in the Channel, and forming the smallest of the Norman group. The weather being so propitious, our voyage was soon accomplished, not, however, before we had perfectly satisfied ourselves of the excessive danger of the passage during stormy weather, or under the guidance of unskilful pilots. Indeed, as a proof of this, we were informed that few native families existed who had not lost at least one member of their household in these rough waters, and gazing around on the innumerable rocks jutting out of the ocean, we could not sufficiently admire the daring and enterprise of these early northmen, who in their frail barks so fearlessly explored these wild shores.

The approach to Sark is very grand, an almost insurmountable barrier of rocks, rising between 200 and 400 feet perpendicularly from the sea, and giving it the appearance of some huge castle floating along the deep. The eastern side is defended by submarine shelves of rocks running out in some places a mile from land, and producing great overflows and eddies, and so strongly fortified is it by nature, that a handful of men, with the requisite works, would amply secure it from all attempts at invasion.

We now rounded the northern point of the island, and looked somewhat anxiously amidst the craggy precipices for a landing-place, as nothing in the shape of a harbour was to be seen. At length, however, the passengers began to bestir themselves; the anchor was dropped, a boat or two pulled alongside, and in a short time our entire party were safely landed on a pebbly beach, shut in from the land by inaccessible cliffs. We now found that our path lay through a tunnel cut in the rock, and forming the only road on this side into the interior. A very primitive cart received our baggage, and the no less primitive driver conducted us up a toilsome ascent devoid of much picturesque beauty, until he finally deposited us outside a pretty cottage where we were informed lodgings were procurable, and after satisfying ourselves on this important point we began to make ourselves as comfortable as our limited establishment would admit. soon found that our habits would not be very luxurious, judging at least by our first dinner, which consisted of ham and eggs washed down by copious draughts of rough cider. However, we had taken the precaution to bring with us a few bottles of stronger waters, with which we soberly qualified our acrid beverage, and, lighting our cigars, strolled out to view our new abode. It was a lovely midsummer evening, with that gentle cool breeze which so delightfully tempers the heat of the day in these islands, and as we rambled along the cliffs drinking in the grateful air, and listening to the distant voices of some fishermen preparing for their night's excursion, the almost unbroken stillness, the picturesque precipices rendered doubly so by the rich moonlight, which invested their grandeur with a specious of mysterious awe, and the gentle break of the ocean against those time-worn crags, altogether formed a picture of wild solitude which amply repaid us for our somewhat homely fare, and made us fully enjoy the welcome repose of our snowy beds. Next morning we prepared to explore the island, and during our stay were so much delighted with the scenery, and, moreover, derived such bodily advantage from the invigorating health-climate, that we have thought a short sketch of this almost unknown spot might not prove unacceptable to our readers, more especially as the importance and beauty of the Channel Islands are becoming every year more fully known to the thousands of summer tourists who flock thither.

Sark (or, as it is written in old documents, Sercq and Cercq) is about six miles distant from Guernsey and twenty-four from the coast of France, and is the fourth in size of the cluster, being three-and-a-half miles in length and one-and-a-half in width, and as it consists of high table-land, the appearance from the sea is that of a barren rock. Its history is not particularly noticeable. In early times it formed part of the territory of the Unelli, near modern Coutance, and passed with the rest of the duchy of Normandy over to the English crown at the period of the Conquest. The remains of a monastery, founded by St. Maglorius in the year 565, were recorded to be in existence 800 years afterwards, and their site is supposed to be occupied by the present manor-house, the residence of the Seigneur. In the year 1349 the monks left their retreat, and the few remaining inhabitants devoted themselves to piracy until they were finally extirpated by an English vessel from Rye, in Hampshire, in the year 1356. It appears from the Jersey historian, Falle, that these pirates were in the habit of decoying strange vessels to their shores by means of false beacon-lights, and then plundering them; and to such extent did they carry their marauding practices, that the English merchants resolved to exterminate their troublesome foes. Accordingly a ship was equipped for the purpose, and sailed to Sark, when the crew, under pretence of the death of their captain, begged the inhabitants to allow them to bury their deceased commander. This was agreed to, on condition that the sailors should come on shore unarmed. The coffin was then carried into the little chapel, but instead of a corpse, it contained a quantity of arms; and during the absence of the natives, who, under the impression that their visitors were fully engaged in their religious rites, had, as usual, proceeded to plunder the ship, the English sallied forth from their sanctuary, and put to death the whole of the scanty population. So our readers will perceive that the scheme of the Trojan horse has not been utterly forgotten by warriors of later times.

From this period, for the space of nearly two hundred years, the place is supposed to have been depopulated, all desolate and bare. Its dwellings down, its tenants passed away, until the year 1549, when nearly four hundred men arrived from France and took possession of the island in the name of their king. They erected two fortresses, the remains of one situated at the Coupée being still visible; but soon finding themselves in an almost helpless state of starvation; they abandoned the place, taking care, however, to leave a small garrison behind them. A few years afterwards, some Flemish vessels arrived in the dead of the night, landed their men, and quietly captured the island, which they presented to Queen Mary. We next find a certain Seigneur de Glatney, in Normandy, attempting to colonize it: but the real final settlement took place in the year 1563, under Helier de Carteret, Seigneur de St. Ouen, in Jersey. This enterprising gentleman, with his no less heroic wife, having obtained a grant of Sark in perpetuity from Queen Elizabeth, at a yearly rent of fifty sols tournois, set zealously to work, despite the numerous obstacles which presented themselves, to cultivate their new possession. A minister of the Reformed Church was appointed to preach the Gospel to the little colony, who have ever since had their spiritual wants carefully attended to. De Carteret now presented himself at court, and so well pleased was the queen with his exertions, that she gave him twelve new pieces of artillery from the Tower of London for the defence of his little kingdom.

Under his rule, the island flourished greatly. Gradually the land became divided into sieurships, farmhouses were constructed, roads formed, agriculture attended to, the tunnel leading to the principal landing-place at the Creux was pierced, and the entire aspect changed. Since this period, few events appear to have ruffled the surface of this primitive society. At the capitulation of Jersey by the Royalists in the year 1651, we find a clause containing the following words:-"It shall be left to the Parliament's good pleasure to allow the Seigneur of St. Ouen to compound for the island of Sark."

Early during the last century it passed from the de Carterets into the possession of Dr. Milner, Bishop of Gloucester, who sold it in 1780 to a Mrs. Susannah le Pelley, in whose family it has remained until within the last few months, when it was again transferred into other hands.

It is a curious fact, that this little patch of territory should be almost the only remnant of feudalism in our country. The law of primogeniture obtains full sway here, and in case of failure of sons the eldest daughter takes the whole of the estate, so that the properties have never multiplied, but consist of the same number of estates as at the original settlement.

The Seigneur is the chief officer of his militia, consisting of from eighty to ninety men, who are considered the best marksmen in the Channel Islands, and he enjoys the rank of a lieutenant-colonel. He is also the supreme magistrate, and appoints a sénéchal, a prévôt, a greffier, and overseers, to hold courts for the determination of petty offences, grave charges coming within the jurisdiction of the Royal Court of Guernsey. Once a year the seigneur and his forty sieurs, i.e. the possessors of the forty estates, meet in their little parliament for the purpose of local government and despatch their weighty affairs according to the approved plan of majorities, the lord, however, retaining the power of annulling their decisions.

One of the most remarkable objects in this romantic island is the Coupée or natural bridge connecting Great with Little Sark. This narrow isthmus is between 400 and 500 feet in length, and from five to eight feet in width. Its altitude is 384 feet from high water-mark, being greater than that of St. Paul's Cathedral, and we can imagine few sights more magnificent than the view from this dangerous pass on a stormy day. The illimitable ocean stretches away before you unbroken, save by the neighbouring islands and the French coast. A few vessels in the distance straining every nerve to buffet the raging waters relieve the desolate monotony, while the dark red sails of the Sark fishing-boats prowling along the coast take back the imagination to those early times when their ancestors were the terror of the surrounding seas.

The wind howls along the fearful pass and renders a cool head absolutely necessary in order to stand the dizzy height, but if you can trust yourself to look down, the tremendous sheet of foam dashing with all the fury of an Atlantic storm directly beneath your feet, the roar of the mighty breakers, mingled with the howling gale and the shrill cries of a myriad sea-gulls wheeling about in the troubled air, render the Coupée of Sark one of those sights a man never forgets.

After passing this singular bridge, we found ourselves on an extensive common, and were presently conducted to one of the lions of the place, called "Le Pot," a circular quarry of considerable depth, opening at the bottom through an archway to the sea. As the tide was high and the day tempestuous, the water boiled as if in a cauldron, throwing up clouds of steaming spray, which materially increased the natural grandeur of the scene. The cliffs are bold and dangerous in this part of the island, but one of the principal features, at least in the eyes of our cicerone, were the silver mines, commenced some few years ago by the late Seigneur. He informed us that the idea originated by a gentleman shooting a rabbit, which fell over the precipice into a creek, and on searching for his spoil, he was somewhat astonished to find, in addition, several stones of rich argentiferous lead. Soon after this a company was formed, miners from Cornwall were engaged, shafts sunk, rocks blasted, in order to construct a landing-place, and the works were carried on with considerable vigour. But despite the mineral richness and the rare combination found here of muriate of silver, only known to exist in some of the South American mines, the undertaking appears to have been but partially successful.

Having examined this portion of the island, we recrossed the Coupée, and visited the Creux Terrible, another of those curious chasms in the shape of a pot, about 150 feet in depth, and supported, apparently, by columns resembling the piers of a bridge, through which the ocean dashes into the gulf with terrific grandeur. On our return, we could not but remark the absence of sheep on the fine downs so admirably adapted for this purpose, both on account of their extent and the quality of the herbage.

The air is peculiarly bracing and pure, and although it may seem at first sight somewhat paradoxical, it is nevertheless true, that the climate differs materially from that of the other islands, and is incontestably superior in its invigorating qualities. As a proof of this we might adduce the longevity which the natives attain; for we find that out of a population of 700 souls, forty-two had reached upwards of seventy years of age, some of the number varying between eighty and ninety-five, and were active, hardworking people, with their faculties unimpaired. This list was drawn up in the year 1844, when there was no resident medical practitioner in the island. Now, although this may excite a laugh at the expense of the profession, still most reasonable men will allow that any community living without a surgeon to attend to their accidental and natural ailments will in all probability lose several lives through mere absence of medical aid. Then again, the nature of these poor persons' avocations, consisting for the most part of fishing in the dangerous seas around, cuts off a number of active young men by shipwreck; so that taking all things into consideration, the salubrity of the climate will be fully established by the above fact. In addition to this, the scenery is more magnificent than that of the other Norman isles, and will afford ample delight for a few days at least. There is a comfortable little hotel, where the visitor will meet with civility and moderate charges, besides several farmhouses, where lodgings are let during the summer months. If the party be numerous enough, the best plan is to engage an entire house, which may be done for about £1 a week. Provisions above the ordinary back fare are brought daily from Guernsey by the cutters, which likewise carry the mailbag. The natives are quiet, honest people, speaking a patois of the Jersey French, which is not very difficult to understand. We found them invariably civil and obliging, and on inquiry learnt that robberies and other crimes are scarcely known among this primitive people. Indeed, during the whole period of our visit we never thought of locking the house-door at night, as such precautions are entirely unneeded.

We must now conclude this hasty sketch. Some of our readers may be tempted to extend their summer rambles to this little island; and if economy, exhilarating air, fine romantic scenery, scrambling over rocks, picnicking in caves, admirable sea-bathing, boating excursions, and a sort of Robinson Crusoe mode of life, can compensate for the total absence of society, then we feel satisfied they will not regret spending a week or even longer amongst the lovely bays and green valleys of Sark.

For more biographical information on Eliza Cook, see The Confidential Clerk