The History of New Holland, 1787

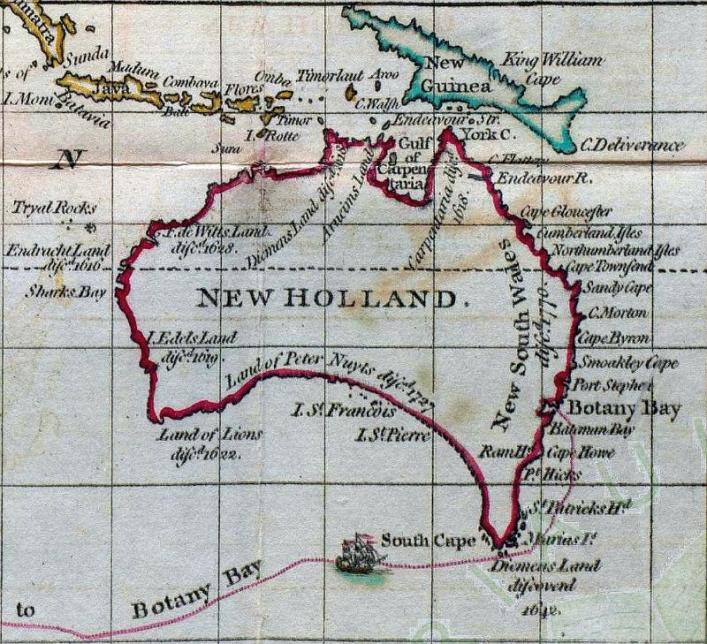

Eden, William, 1st Baron Auckland (1744-1814), The History of New Holland, from its first Discovery in 1616, to the present time. With a particular account of its Produce and Inhabitants; and a Description of Botany Bay: also, a List of the Naval, Marine, Military and Civil Establishments, to which is prefixed, An Introductory Discourse on Banishment, London, 1787, Printed for John Stockdale, opposite Burlington-House, Piccadilly, 1787. The map, a plate from the book, shows the route to Botany Bay. This volume came to the Priaulx Library as part of Elizabeth College's Le Marchant Library Collection.

The plan adopted by the British government of transporting criminals of a certain description to Botany bay, in New South Wales, discovered in the year 1770, by Captain Cook, has been so long and so generally the subject of popular discussion, that every information relative to a country so extraordinary and so little known, it is presumed, will be acceptable to the Public.

So wrote William Eden in 1787 as the opening paragraph of the Preface to The History of New Holland, a critical survey of the existing literature on Australia, from Dampier to Cook, with extensive passages quoted from the originals, which volumes, he remarks, might well be too costly for most people to obtain. A long-time friend of William Pitt, Eden was charming, religious, and a smooth operator; a reformer, politician, and diplomat, he was influential in remodelling the laws relating to punishment and penal servitude in the late 18th century.

The book was written as the first convict expedition to Botany Bay was under preparation. It lists the ships with their principal officers and offers the reader two beautiful maps; one, of the journey to Botany Bay as it was to be made by the convicts and their masters; and two, New Holland, as Australia was called then, as much as was known of her. This second map is quite extraordinary, displaying the entire coastline of the continent in great detail, with the interior absolutely blank.

Eden writes about all aspects of Australia, its flora, fauna, and native people, and quotes at length from his sources, usually Captain Cook. In examining the history of Australian exploration he begins with the Dutch Captain Pelsart in 1616, regrets being unable to have access to Tasman's diaries, and proceeds to Dampier.*

He mentions also another [quadruped], which appeared to him to be a sort of racoon, but differing from those of the West Indies chiefly as to their legs; for these of New Holland have very short forelegs, but jump as the rest of their species do, and are, like them, very good meat. The description of this beast would naturally induce one to suppose it of the same kind with the leaping quadruped seen by Captain Cook's people on the coast of New South Wales, which is called by the natives kangooroo [p. 13]He lists some of the words that the indigenous people taught the original explorers, including a list from Sydney Parkinson, a young man whose journalistic abilities are highly rated by Eden but who unfortunately died at sea on Cook's voyage:

To dance, Mingoore; to swim, Mailelel, to sleep or rest, Poona; Chaloee - An expression of surprize; Yarea and Charo - Words uttered with a mixture of pleasure and surprize, on seeing the whiteness of the skin of some of our people, who had taken off their clothes in order to bathe.

Many criminals in Britain, even petty ones, would in Eden’s day be sentenced to the death penalty or transportation. Before the American wars put a stop to it, troublemakers were exported to the colonies, and prisons were relatively empty and their maintenance expenses low. Many factors were nevertheless exerting pressure upon the authorities of the time to ameliorate the prisoner’s lot and to make punishments less severe. In public opinion, too many offences had been classified as capital, reflecting the penal system’s gradual widening to cover all aspects of life, perhaps a result of the necessity felt by the authorities of keeping the growing working classes under control. The loss of the favoured destination for transportation meant an expanding prison population lodged at the taxpayer’s expense, and too few prisons too keep them in, while various reports and exposes of the dreadful conditions in some of Britain’s jails caused unease. The deep religious convictions that permeated all classes led inevitably to a more humanitarian approach to punishment and the view that its desired effect upon the individual prisoner was their penitence and improvement of their moral well-being, through religious instruction and hard work, this conveniently also being the most beneficial outcome for society at large.

It should be noted that although these philosophies were no doubt shared by the educated classes in Guernsey, the system of punishment in force was not the same, having remained unchanged for centuries. Norman-style banishment was quite usual, transportation was not, and although the latter began to appear in the Royal Court unannounced in the early 19th century, it remained an infrequent punishment. Despite the intense religiosity in Guernsey at the time, the authorities did not get around to facing up to the question of prison reform until 1828, when they began plans to erect a 'House of Correction.' A new prison had been built in 1811; previous to that ordinary prisoners had been housed in cramped and unsuitable conditions in Castle Cornet, or the Town or Country Hospital. French prisoners-of-war had their own 'French Prison' (Alderney had no prison, and prisoners were the responsibility of the Alderney Prevôt until they arrived in Guernsey.) There was not much crime in Guernsey; recidivists had often been 'banished,' or deported for a number of years, whether native or stranger, and this practice had continued despite occasional misgivings.

The author: William Eden, 1st Baron Auckland

William Eden was born in 1744, the third son of a County Durham baronet. After Eton and Christchurch he was called to the bar in 1769, but his ambition soon became evident when he published Principles of Penal Law in 1772. His was a humanitarian but conformist view and attracted him a good deal of attention, following in the footsteps of other famous reformers of the period:

The immediate end of punishment was, they all agreed, to deter future crime; and, on a wider scale, they concurred that punishment ought prominently to protect the liberties of law-abiding citizens. In practical terms this agreement amongst many writers of the early to mid-1770s displayed itself in their showing a collective distaste for imprisonment as a punishment. By 1778, however, [they] ... had come to place great value on the possibilities offered by imprisonment as a means of achieving their theoretical ends of reformation, disablement and example.¹

A generally over-achieving politician and diplomat (with a very strong interest in American matters), Eden was, however, prone to changes of mind. In 1776, whilst a member of the Board of Trade, Eden put together the Convict Act, which asserted the potential usefulness of convict labour and created the prison hulks, or floating prisons, to cope with those prisoners who could no longer be transported to the American colonies, significantly allowing for remission of sentence upon 'signs of reformation.' His aim and those of his fellow penal reformers was always to find an acceptable and practical alternative to the death penalty and transportation; these prisoners dredged the Thames instead. Other elements began to creep into their philosophies, and in 1779 he, along with the Quaker John Howard and redoubtable Oxford professor William Blackstone, shaped the Penitentiary Act of 1779.

As an alternative to transportation this provided for the building of two penitentiaries, one for males and one for females, where 'solitary Imprisonment, accompanied by well regulated labour, and religious Instruction' 'might be the means, under Providence, not only of deterring others from the Commission of the like Crimes, but also of reforming the Individuals, and inuring them to Habits of Industry.'²

Transportation to Botany Bay was accepted as a potential punishment in the later drafts of the Act, perhaps because (as Eden himself admits in the Preface to this work) the prison hulks were proving too expensive to maintain. The practical Eden was always ready to compromise; better transportation than death, better Botany Bay than Africa or the mines, as others had proposed, alternatives that he viewed as nothing more than a punishment by slow death. Preparations began for the building of the penitentiaries began but momentum was lost, and political will was not found again for many years. This helps explain why a man who in 1779 formulated an Act of Parliament originally proposing simply to build penitentiaries on British soil to reform prisoners through religion and hard work wrote an introduction to Australia in 1787, the year in which transportation was resumed, with a Preface in which he attempts to help the public understand more about the lenient nature and appropriateness of this new punishment. In this Preface, however, and in the accompanying Discourse on Banishment inserted before the main text, there is still a marked lack of enthusiasm for transportation; for him, it is simply better than the alternatives, and he has failed to find the answer. [DAB]

Coincidentally, in 1785, when Eden undertook a diplomatic mission to France, his secretary was Etienne Gibert, later the minister of St Andrew's Church in Guernsey; he, as a Protestant convert and refugee, had not set foot in his native country for fifteen years.

* Eden's timeline is historically inaccurate.

¹ Tony Draper, 'An Introduction to Jeremy Bentham's Theory of Punishment'. Bentham shared Eden's interest in penal reform.

² Throness, Laurie, A Protestant Purgatory, Theological Origins of the Penitentiary Act, 1779. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2008. A very interesting perspective on 18th century penal reform and William Eden. The author points out that as yet no biography of Eden has been written, despite the great deal of original material that exists.