The institutions of the island of Guernsey and women's right to vote in the island

26th June 2015

The observations of a French legal expert published in La Gazette de Guernesey, 28 June 1913. 'One can never be quick enough to put right an injustice, and it is unjust to exclude women from undertaking public duties.' Jurat F J Jeremie's was but a lone voice, and duly ignored.

Monsieur Fernand Daguin, advocate of the Court of Appeal in Paris, brought to our notice a Note concerning The Island of Guernsey and the electoral rights of women in the island:

[Introduction to Guernsey and Courts &c.]

Municipal administration is entrusted to the Constables, to the Douzaines and to the Parish Assemblies. Two constables are elected annually in each parish. Their responsibilities include local policing; in Town and in a few of the parishes, they are in charge of policemen. Troublemakers and crime suspects are brought before them and in serious cases they can order the suspects to face trial. They also look after refuse collection, improvements in municipal services, and collect certain taxes, such as horse tax, dog tax, cycle and car tax, &c. The oldest of them chairs meetings of the Douzaine.

The Douzaine is the administrative council of the parish; there are twelve members elected every six years by the parishioners. In the Town, only those men who are worth more than 35 quarters of rent (i.e. worth at least 21,000 francs) are eligible to be Douzeniers; in the country parishes, they must be worth at least 7,800 francs, or 15 quarters of rent.

The electoral body of the parish consists of anyone worth at least one quarter of rent, that is to say who possesses property or goods to the value of at least 600 francs. They elect parish officials by majority vote. States Deputies are elected by the Douzaines, that is to say, by the parish councils.

Up until 1892, only men had a right to vote in parish elections.

In 1891, the Royal Court considered favourably a proposal [projet de loi] to allow women, under certain conditions, to vote in parish elections. They passed this over to the States and it was debated and voted on on 2 December 1891.

During the debate jurat Jeremie put forward an amendment to allow women to undertake some parish duties.²

I appeal to the [church] ministers present at this sitting; women are quite capable of dealing with some parish duties better than any man, looking after the poor, for example.

When jurat Tardif suggested that they should wait and see how women dealt with the rights that were about to be afforded them [i.e. to vote in parish elections] before going as far as that, jurat Jeremie replied forcefully:

One can never be quick enough to put right an injustice, and it is unjust to exclude women from undertaking public duties.

Despite this, the projet was passed and the amendment rejected, by 27 votes to 7.

This was the law as drawn up:

LAW GIVING WOMEN THE RIGHT TO VOTE IN PARISH ASSEMBLIES.¹

1. Women with no husband, and women legally [quant aux biens] separated from their husbands , who are taxpayers in the parish, may attend and vote in parish assemblies of taxpayers and of the Heads of Families.

2. Women who have no husband and those who are legally separated, who pay parish rates, may attend and vote in parish assemblies of the Heads of Families (i.e. property owners).

3. Women may not undertake any parochial duty.

As is evident from this, the rights accorded to Guernsey women were far from generous. Only unmarried women and widows, or women who were legally separated from their husbands, had the right to vote; in addition, the right was limited to parish matters. Women could from now on contribute to discussion of, and vote on, matters of street lighting, policing, public assistance, and in a general way, all parish concerns; they could vote for parish officials such as constables, douzeniers, poor officers &c, but could not be employed in any parochial or other public duty, nor could they help to elect jurats or the King's Prévôt.

However, such as it was, the law was enacted and no-one abused it or complained about it. Did it produce any notable results, however? On balance it seems doubtful.

According to the information kindly supplied to me by Monsieur [Theodore] de Mouilpied, few women actually make use of the privilege bestowed upon them. It seems that it is very unusual for a woman to attend a parish assembly or to vote. Moreover, this indifference to public affairs is shared by the men, who are reluctant to take part in public life, or to exercise their right to vote. Guernsey people, who enjoy independent governance, privileges and freedoms that go back to their Norman ancestors, have no interest whatsoever in outside affairs and hardly bother with local politics. They cultivate their crops, raise their cattle, and try to make as much money out of exporting their produce as they can. They do not worry much about the rest.

It seems very unlikely, then, that they will be thinking in the short or long term about extending the electoral rights of women, or to allow them to take on parochial duties, as was the wish of jurat Jeremie, in his speech in 1891. [From the French.]

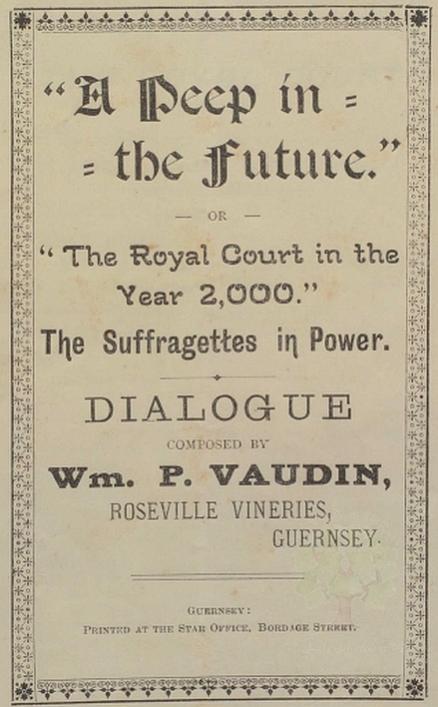

The Library has just received through donation a pamphlet, the cover of which is illustrated above, written by Wiliam Vaudin, in which a Royal Court made up entirely of 'ladies' lets off a set of racially and socially stereotyped miscreants for various domestic crimes. To say this pamphlet is 'politically incorrect' is an understatement. It may well date from 1913, the time of the following letter to the Star newspaper:

MILITANT WOMEN

To the Editor of the Star.

Sir,—May I, as a visitor to your beautiful island, claim the hospitality of your correspondence column?

Though Guernsey is not directly concerned with the cause of 'Votes for Women,' I find much interest manifested in the question here. As far as I can ascertain from the local press, hostility is felt towards the militant methods adopted by certain sections of the women who are struggling for their political freedom. May I give one of the many instances which might be cited to illustrate how militancy is forced upon the women by those who condemn it?

I called last week at one of the chief newsagents in the island, and ordered The Suffragette. I was told that it would be obtained for me in a few days' time. After an interval I called several times to see whether the paper had arrived. Last night I received a note from the bookseller to the effect that the agents refused to procure The Suffragette.

Now, sir, may I put it to you and your readers, that constitutional propaganda is a recognised means of advancing the cause. Women are constantly being barred from executing their constitutional rights. They are even denied, at any rate by the present Government, the elementary right of carrying into practice that clause of the Bill of Rights, which states that it is the right of the subject to petition the King or King's Ministers. It is when this, and many other constitutional avenues are closed to the women, that they seek for other means of bringing pressure to bear on the Government.

Had this Liberal Government acted up to its professed principles of democracy, militancy would have been unnecessary. The Goverment denies constitutional progress to the Women's movement; it is boycotted in various other ways, and militancy is the result.

In conclusion, and thanking you for your courtesy in allowing me space in your paper, may I ask one question? Does a bookseller's agent usually reserve the right to refuse to procure literature of which he personally does not approve?

I am, sir, yours obediently,

E B RICHMOND,

Grange Road,

Guernsey, August 20, 1913.

¹ [Billet d'Etat, Friday, 5 February 1892, p. 7].

² The author based this on Le Baillage, 5 December 1891.

It was not until 1919 that the States voted to allow women to undertake parochial duties.

The Star June 1919

The States: Women in Parochial Offices

On May 14 the States adopted for the first time the Projet de Loi making women eligible for parochial offices and they were now asked if they would adopt it for the second time. According to Constitutional Law, it is necessary that any change in the Constitution must be adopted by the States three times.

Delegate MORGAN asked whether married women could not sit on the Education Committee or Poor Law Board.

The PRESIDENT: married women are supposed to be under the control of their husbands, and in Court when passing Contracts they have to take an oath they had not been constrained to carry out the deed by their husbands. Personally he had often thought the oath should be reversed (loud laughter.)

Delegate MORGAN asked if it was not possible to bring the Law more up-to-date, and allow married women to become eligible.

The PRESIDENT: According to law a married woman is not an independent person.

Delegate MORGAN moved an amendment that the matter be postponed for the consideration of the admissibility of women.

Jurat CAREY said he was in favour of that, as he considered married women more valuable than single women.

Jurat DE GUERIN said the proposal would open such a large question and he thought they should vote on the proposition.

Delgate Morgan's amendment was not seconded, and the States adopted the Projet for the second time.

The first woman to hold the office of parish constable in Guernsey was Diana Meldrum, who was elected to the position in St Peter's parish in 1975. See her obituary in the Guernsey Press, 21 July 2016.