Thomas Andros' Commonplace Book

Thomas Andros' Commonplace Book, by the Seigneur of Saumarez Manor, from a family 'whose penmanship was far from good;' a handwritten pamphlet of herbal medicine and fruit-growing, dated 1589, Guernsey, and an exploration of other texts quoted in it.

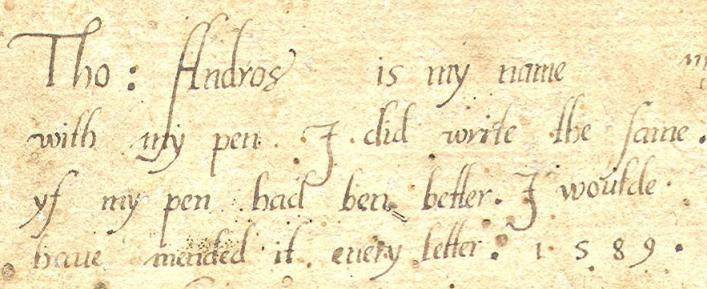

The Priaulx Library has amongst its collection a very fine document, known as The Commonplace Book of Thomas Andros. It is a pamphlet of 16 pages, written on paper, with one extra loose leaf inserted. On the front page is written:

Tho: Andros is my name

With my pen I did write the same

If my pen had been better

I woulde have mended it every letter. 1589

The booklet is very carefully written in an Italic hand.This style of writing came into use in the middle of the sixteenth century, having been adopted on the Continent by the Humanists, who wished to emulate the authors of the classical period, and its usage here in 1589 may indicate a liberal education and a continental influence. The style of the hand, however, in that the letters are not cursive but are printed, would seem to point to the schoolroom.The rhyme on the front cover quoted above was used at this time and for at least two hundred years afterwards by children to practise writing and indicate ownership of a book; there are many examples in collections. Children were often encouraged to make careful copies of books, not only to improve their handwriting, but because books were scarce; adults often continued the practice.

Thomas Andros was born and lived at Saumarez Manor, of which his father John was Seigneur. The Andros family were originally wool merchants from Northamptonshire, and had Frenchified their name from Andrew[s]. The first John Andrew had come to Guernsey in 1545 as Lieutenant Governor, with the Puritan Governor, Sir Peter Mewtis; he was probably already married to Judith De Saumarez. The De Saumarez line had given way to the Andros’, amidst much rancour and litigation; the Andros' would eventually sell the Manor back to the Saumarez family in the 18th century.¹

The booklet is written in French and is divided into roughly two sections.The first section covers medical and cosmetic matters, the second gardening, in particular the cultivation of fruit trees.This article, however, is concerned with a loose leaf inserted in the booklet. This leaf contains various seemingly unrelated lines of verse, the majority of which is in English, amongst which a few of the words are repeated ad hoc. At the top of the page is a sonnet, written in secretary hand. This style of writing is the most commonly used during the period and is perhaps what we most associate with the Elizabethans. The Italic hand, however, was used alongside it by those who favoured it and its political implications; the two did not begin to mingle until the middle of the seventeenth century, when the cursive writing we use today began to develop out of them. The Italic hand is relatively easy for modern eyes to read, as contemporary handwriting is based upon it; the secretary hand is probably more difficult for most people.

...most writers retained the basic characteristics of the hands (often both a secretary and an italic hand) which they first learned, maybe fifty years earlier, and their writing master might have formed his hand yet fifty years earlier still--so precise dating from the hand alone can be hazardous.²

E. B. Moullin noted in his article (Report and Transactions of La Société Guernésiaise, 1950) on Jean Guille's notebooks (also part of the Priaulx Library collection):

In a manuscript book of Pedigrees written, about 1880, by the Rev. H le M Chepmell, DD, is the remark 'The Guilles were remarkable for writing a good hand. One of the family who was one of the earliest clerks in the Bank of England made a copy of the authorised version of the Bible, for the use of Queen Ann. The family of Andros, on the other hand, had no such reputation. Though it could boast of men of higher mark, its penmanship was far from good.'

The sonnet, Against a slanderous tongue, was written by Thomas Tusser (d. 1580), who first published his extremely popular 500 Pointes of Good Husbandriein 1557. He issued revised and augmented editions until 1577, which continued to be reprinted until 1744. From the 1573 edition also comes the rhyme

Some slovens from sleeping no sooner be up, but hand is in aumbrie³, and nose in the cup.

Thomas Tusser’s book is not the main source of the information in Thomas Andros’ booklet; Tusser wrote in English, entirely in verse, and concerned himself particularly with agriculture, as well as herbal medicine. He added several sonnets at the end of his book; the sonnet that has been copied out is said to be the best. Tusser died virtually a pauper, despite urging thrift and economy and selling so many copies of his work; he was known for his aimiable nature, but as Fuller in his Worthies of Essex explained: 'Thomas Tusser spread his bread with all sorts of butter, yet none would stick thereon.'

The rest of the couplets that are written out are religious in nature. Several are based on Ecclesiastes and are taken directly from Richard Day’s Book of Christian Prayer of 1569 (revised 1578),4 what one scholar has called 'the only examples of Elizabethan prayer-books de luxe to appear in Elizabethan England.' The woodcut illustration of Elizabeth at her devotions in both editions, and the provision of prayers for the Queen herself to say (in the 1569 version), helped secure it for a while the nick-name Queen Elizabeth's Prayer Book.5 Heavily decorated with borders and figures, it included a medieval 'dance of death,' which was complemented by the couplets that have been copied out in our booklet. Richard Day was the son of the master printer John Day, who produced Foxe’s Book of Martyrs.6 The 1578 second edition of the prayer book replaced continental prayers with material by Knox, Foxe, and Calvin, and included prayers for the Queen herself. A unique copy was printed for Elizabeth with those prayers in the first person. One of the prayers includes these words, no doubt in reference to the Huguenots of France and Flanders:

And for so much as it has pleased thee to be so good and gracious to our sovereign Lady,and to do her the honour, that, whereas other realms are in grievous troubles, thou hast given her rest in this her land, and sent hither the bowels of thy Son Jesus Christ, to have refuge here in their oppressions: grant her the grace to be a true nourisher and nurse, of all such as are thine, according to the saying of thy prophet Esau, so as she may have a true compassion both of them that are here, and of all others.

Another is entitled A Prayer for the afflicted and persecuted under the tyranny of Antichrist, which has its origin in Elizabeth’s aid to the French Protestants in 1562.

The other verses from Andros' exercises are in French. One,

Amour de richesse trop peu dure

Fol est celui qui s’y assure.

seems to correspond to the verse from Day's dance of death:

Riches, nor treasure, avail no thing:

For death to earth all doth bring.

As death in this world hath the victory:

So by death we hope to enter God's glory.

especially so since the metre is similar and following two lines are directly quoted, as is the next verse:

[Death takes no bribe of wealth: Death forceth not long health.]

Time to live, and time to die, God grant us live eternally.

No hope for better, no place for worse. This was a Puritan sentiment, but was in use in the sixteenth century.7

O dieu, leve toy a grand erre

Et t'en vien gouverner la terre

Car a toy de droit appartient

Tout peuple que terre soustient

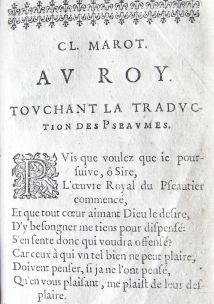

This French stanza at the bottom right forms the last four lines of Psalm 82 from the 'Geneva' Psalter.The complete edition of the Calvinist Book of Psalms was published in Geneva in 1562, as Les pseaumes mis en rime françoise par Clément Marot & Théodore de Bèze. 99 of the psalms had been paraphrased by the Norman poet Clément Marot at the behest of Calvin himself, and 101 by Théodore de Bèze, after Marot’s death.The music was written in the form of chants especially for the Psalter by Louis Bourgeois and others; Calvin appreciated the beneficial effect that music could have upon the worshipper, but rejected the use of accompanying instruments as he felt they belonged to the Old Testament.

The production of the Psalter was an enormous undertaking.

Théodore de Bèze had obtained a 10-year royal warrant from Charles IX and so the Psalter, rather than being published in secret, became one of the most extraordinary print undertakings of the century. Antoine Vincent, a rich merchant and bookseller in Lyons and Geneva, was put in charge of the printing; from a base of 45 workshops around the country ... this extended web of printing, including 24 printers in Paris alone, demonstrates the Calvinist Psalter’s immense popularity. More than 30,000 copies were sold in the first year alone ...8

The Priaulx Library has a 1654 copy of the Psalter, which was bought in Jersey in 1904 (see right and above). At the end of the book is included the Strasbourg ritual, which was a form of prayer first written by Calvin in 1542: La Forme des Prières Ecclésiastiques. Avec la manière d’administrer le Mariage, et de la visitation des malades. This ritual was followed by French refugees in London and by some in France. Although the Channel Islands had a French version of the Book of Common Prayer specifically prepared for them at the command of Edward VI in 1551, which was influenced by Calvin, it is thought that the Huguenots here in the Channel Islands preferred to use their own. This copy of the Psalter, although it is missing its imprint, includes a calendar of important dates for French Protestants, commemorating, for example, the death of the Duke of Guise and the Prince of Condé, the assassination of Henri IV, death of Martin Luther, the siege of La Rochelle and many sixteenth-century massacres. It also includes a list of the dates of principal fairs in France. There is no indication to whom it belonged, though there were many Huguenot refugees resident in both Jersey and Guernsey. This version of the Psalms was enormously popular in France, and not in any way proscribed (it was associated with the Reformists only because its translators were) so it is not possible to deduce from the inclusion of part of a psalm from it in the booklet alone that the Andros family was particularly inclined to follow Calvinistic worship.

The French translation of the Book of Common Prayer was put together in 1549 for Edward VI and translated in 1551 by Francois Philippe under the direction of the Bishop of Ely. The 1551 edition was intended to be used in the Channel Islands and Calais. It is, however, extremely rare (there may be only one extant copy, in Lambeth Palace Library); the Priaulx Library does not have a copy of the revision of 1616 either, from which one might infer that the French Book of Common Prayer was very little used, with even non-Huguenots, like the Andros family, using the Geneva Psalter and perhaps French 'Geneva' Bibles, or the English Book of Common Prayer. The Library has, however, recently acquired a copy of the new edition produced after the Restoration; this was edited in 1663 by a Jerseyman of Huguenot extraction, Jean Durel (1625-1683).

Having been sent down from Oxford for his Royalist sympathies, most of Durel's time from 1642 till 1660 was spent in France and in the French possessions. He returned to England in 1660, and was appointed by Charles II as first minister to the newly established French Chapel of the Savoy, near the Strand, and Dean of Windsor. The Liturgy of the Church of England was here first read in French on Sunday, July 14, 1661. The same day, in the morning, Durel preached in French a sermon on “The Liturgy of the Church asserted.” This sermon was published in English as an appendix to a larger work of an apologetic character, entitled: A View of the Government and Publick Worship of God in the Reformed Churches beyond the Seas. Wherein is shewed their Conformity and Agreement with the Church of England, as it is established by the Act of Uniformity. By John Durel, Minister of the French Church in the Savoy, by the special appointment of His Majesty.9 The Library also has a copy of this volume.

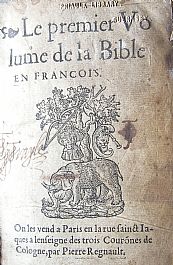

The earliest Bible in the Library’s possession is an edition from 1543 of “La Grante Bible”, or the Bible of Jean de Rély. This was the most popular version of the Bible in France for over a century and had been translated from the Latin Vulgate under the auspices of the French King Charles VIII by his confessor. Although this Bible was strictly speaking not authorised by the Catholic Church, which had forbidden translations of the Vulgate, it was never proscribed or even threatened by the authorities. Charles VIII had reformist tendencies and the Bible’s introduction explains how it was intended to be read by the laity (although there was another version, 'pour les gens simples'); however, it remained what is known as a Bible historiale, or an annotated Bible, with extensive glosses and explanations for the reader, including, for example, the fact that Moses had horns. This edition, of the Old Testament, was printed in Paris by Pierre Regnault, a member of an important printing dynasty whose distinctive family printer's marks always feature an elephant.

At the back is written:

George Ollivier, 1779 - [Voici, toutes les âmes sont à moi; l'âme de l'enfant est à moi comme l'âme du père; [et]] l'âme qui péchera sera celle qui mourra,

which is a quotation from Ezekiel 18:4. As this 1543 printing was one of the last of this Bible, which was 75 years old at the time and cannot be classed in any way as a 'Protestant' Bible, it is curious that it seems to have been used in the late eighteenth century, particularly as it is loosely translated and complete with fantastical annotations.

The Library also has several other Protestant French Bibles in its collection, including copies of the 'Geneva Bible,' the popularity of which amongst French-speaking Protestants lasted for 350 years, and which influenced the translation of the King James' Bible. It was originally translated by Pierre Robert Olivétan (c. 1506-1538), the cousin of Jean Calvin. Calvin wrote the Preface. It was revised by Theodore de Bèze in 1588, although it remained largely unchanged. The Library's earliest version dates from 1678, but is in poor condition and lacks its imprint. The other editions held by the Library are later and are of the next revision, by the French theologian and pastor of Utrecht David Martin (1639-1721), which was first published in Amsterdam in 1702, and a very popular revison of 1724 by Jean-Frédéric Ostervald (1663-1747), who, like many of the foremost Bible translators into French, was Swiss.

¹ Geoffrey Andrews, Thomas Andros' Medical and Gardening Book of 1589, Worcester, Geoffrey Andrews, 1997. This pamphlet discusses the family history of Thomas Andros at length and makes many interesting observations on the content of the booklet.

² See English Handwriting 1500-1700, An Online Course.

³ An aumbrie is a cupboard.

4 Private Prayers: Put Forth by Authority during the Reign of Queen Elizabeth.Edited for the Parker Society by Rev. W. K. Clay, CUP 1851, p. 462.

5 Print and Protestantism in Early Modern England, I.M. Green, OUP 2000, pp. 256-7.

6 Foxe’s Book of Martyrs and Early Modern Print Culture, John. M. King, CUP, 2006, pp. 80 ff.

7 For example, Tennyson, Queen Mary, Act III; The Inner Temple Masque, by W Browne (1615); Puritan elegy (US) of 1672 for Anne Bradstreet by John Norton.

8 See D. Amann, 'Du Livre des Psaumes au Psautier Francais: une tradition poetique et musicale', Le Levant, Bulletin de liaison de l’Aumônerie protestante, n° 5, Sept. 1999, pp. 13-17; and Le Livre des Prières Publiques from the internet History of the Book of Common Prayer.

9 For more on Jean Durel's works, see the internet History of the Book of Common Prayer.

10 For a brief history of French bibles, see the Catholic Encyclopaedia.