Victor Hugo and Guernsey: Algernon Charles Swinburne, King of Sark

22nd March 2019

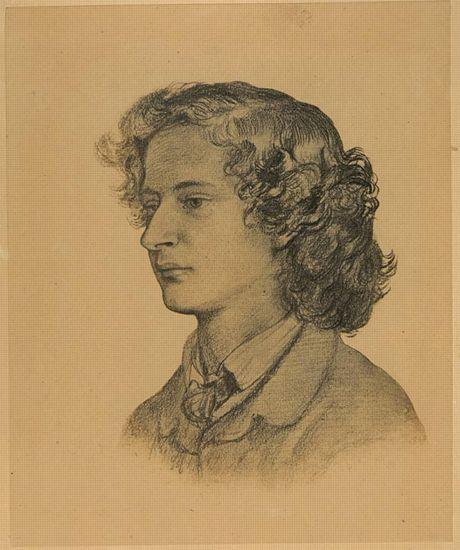

The poet Algernon Charles Swinburne visited Guernsey and Sark in order to follow in the footsteps of his hero and fellow poet, Victor Hugo. He fell in love with Sark and wrote poems describing his time there, so much so that he declared he would like to be king of the island. The portrait of a young Swinburne is by Rossetti — Swinburne had a mane of flaming red hair. It was drawn in August 1860 (image from the Rossetti Archive from a print held in the Delaware Art Museum). There is a selection of his Guernsey poems with reference to Victor Hugo at the bottom of this page. [By Dinah Bott]

The poet and friend of the Pre-Raphaelites Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837-1909) was born on the Isle of Wight. He was possibly Victor Hugo’s greatest Anglophone admirer.

Like Hugo a keen swimmer, he was also both fascinated and terrified by the sea. In 1876 he was swimming off Etretat in Normandy when he was swept out to sea and rescued by future author Guy de Maupassant, who was sailing past in his family’s yacht. Maupassant, who was only 18 at the time, was invited to dinner by a grateful Swinburne and friend, who, mischeviously, hinted that they ate monkeys and indulged in all sorts of other perverse eccentricities. In so doing they seem to have made a great impression on Maupassant, for he went on to describe this episode several times in fascinating and evolving detail, particularly in L’Anglais d’Etretat of 1882 (The Englishman of Etretat.)

After this adventure Swinburne proceeded to Guernsey and Sark, which thrilled him for their magnificent scenery; he was overcome to be able to follow in the footsteps of the master. Hugo had returned to Paris by then, and Swinburne did not in fact meet Hugo until 1882 ... by which time he had become too deaf to hear what he said to him.

‘I have seen Hugo, I have seen Hauteville House, but I would like to see the eagle in the eyrie from which sped the eaglets carrying the thunder called les Châtiments.’

A committed republican, he often describes Hugo in almost Christ-like terms. His relationship with Hugo began in 1863 when he reviewed Les Misérables (very favourably) and sent the review to Hugo. It was well received. At the end of 1865 Swinburne dedicated a play to Hugo, Chastelard, in the most effusive language:

I DEDICATE THIS PLAY,

AS A PARTIAL EXPRESSION OF REVERENCE

AND GRATITUDE,

TO THE CHIEF OF LIVING POETS;

TO THE FIRST DRAMATIST OF HIS AGE;

TO THE GREATEST EXILE, AND THEREFORE

TO THE GREATEST MAN OF FRANCE;TO

VICTOR HUGO.

Hugo wrote to him to thank him:

Hauteville-House, 23 January [1866].

‘Dear Sir, my son, the translator of Shakespeare, is now with me, having just read to me again from your poignant drama, Chastelard. Thanks to him I have a more thorough understanding of its several beauties. He was delighted to translate your work after having translated that of Shakespeare, and he sensed how yours is a continuation of that sublime poetry. Your work is moving and humane to the highest degree. It appeals to the heart and to the soul; to the heart through passion and to the soul through the ideal. You deserve the greatest success with this. It links you gloriously to the great traditions of universal art, while your talent brings honour to contemporary literature. I am deeply touched by the sentiments with which you dedicate this fine work to me. Please accept my heartfelt thanks. Victor Hugo.’¹

It was reported in September 1866 by a visitor to Hauteville House that Hugo kept Chastelard on his smoking-room table next to his own illustrated copy of Les Misérables: high praise indeed – for the dedication, at least. Swinburne dedicated many poems to Hugo and wrote lyrical poetry about Guernsey and Sark; his best-known poem in the islands today is actually his Hugolian ode to the keepers of the Casquets, off Alderney.

‘To Swinburne. Hauteville House, 22 Sept. 1872. O poet mine, I wanted to write to you today, the great anniversary of the republic. I am replying to your superb ode of the 4th September on the 22nd. Twin dates. My son is with me, we are reading you together; he is translating Swinburne for me just as he translated Shakespeare. What a work, your Songs before sunrise! Your article on L’Année terrible got all of Paris talking. You have no doubt read Le Rappel and La République on the subject. You are an admirable and great-hearted man. I have your picture. Here is mine. Dear and noble poet, I shake both your hands. Victor Hugo.’ ²

Swinburne visited the islands again in 1882. He wanted to be ‘King of Sark,’ but had this to say of Guernsey:

‘If you could transplant the loveliest landscape in Tuscany to the centre of the Isle of Skye, even then you would not have quite the equal of Guernsey … There never were such sea-views as here … but no prose or verse except Victor Hugo’s could give you even a faint notion of the island which will always be associated with his name.’

After Hugo’s death he produced a book of literary criticism, A Study of Victor Hugo, published by Chatto & Windus in 1886. It is rather a literary eulogy, ‘an introduction to the study of the greatest writer whom the world has seen since Shakespeare.’

‘In the spring of 1885 the greatest Frenchman of all time has passed away amid such universal anguish and passion of regret as have never before accompanied the death of the greatest among poets … the son of consolation, his burning wrath and scorn unquenchable were fed with light and heat from the inexhaustible dayspring of his love, a fountain of everlasting and unconsuming fire. We know of no such great poet so good, of no such man so great in genius…’.

Swinburne is said to have been consulted by interested Guernsey parties about various documents found in Hauteville House after Hugo’s death and sold on; he pronounced them useless to Hugolian studies; they later were discovered to be Adèle Hugo’s journals.

He died in 1909 in Putney, where he had lived since the early 1880s in almost complete retirement, in the house of his friend Theodore Watts-Dunton.

‘… like his poetry, the personality of Mr. Swinburne appealed scarcely at all to the imagination of the great mass of his countrymen ... That the greatest poet lately living is dead we are certain, and we cannot doubt that much of his poetry will live by virtue of its exquisite music … Non omnis morietur.’

From: In Guernsey

by Algernon Charles Swinburne

VIII

Beloved and blest, lit warm with love and fame,

The house that had the light of the earth for guest

Hears for his name's sake all men hail its name

Beloved and blest.This eyrie was the homeless eagle's nest

When storm laid waste his eyrie: hence he came

Again, when storm smote sore his mother's breast.Bow down men bade us, or be clothed with blame

And mocked for madness: worst, they sware, was best

But grief shone here, while joy was one with shame,

Beloved and blest.

From A Century of Roundels, London: Chatto & Windus, 1883

Victor Hugo: L’Archipel de la Manche

by Algernon Charles Swinburne

Sea and land are fairer now, nor aught is all the same,

Since a mightier hand than Time’s hath woven their votive wreath.

Rocks as swords half drawn from out the smooth wave’s jewelled sheath,

Fields whose flowers a tongue divine hath numbered name by name,

Shores whereby the midnight or the noon clothed round with flame

Hears the clamour jar and grind which utters from beneath

Cries of hungering waves like beasts fast bound that gnash their teeth,

All of these the sun that lights them lights not like his fame;

None of these is but the thing it was before he came

Where the darkling overfalls like dens of torment seethe,

High on tameless moorlands, down in meadows bland and tame,

Where the garden hides, and where the wind uproots the heath,

Glory now henceforth for ever, while the world shall be,

Shines, a star that keeps not time with change on earth and sea.

From A Midsummer Holiday, London: Chatto & Windus, 1884

From: A New Year Ode

(Dedicated to Victor Hugo)

by Algernon Charles Swinburne

XXV

Life, everlasting while the worlds endure,

Death, self-abased before a power more high,

Shall bear one witness, and their word stand sure,

That not till time be dead shall this man die

Love, like a bird, comes loyal to his lure;

Fame flies before him, wingless else to fly.

A child’s heart toward his kind is not more pure,

An eagle’s toward the sun no lordlier eye.Awe sweet as love and proud

As fame, though hushed and bowed,

Yearns toward him silent as his face goes by:

All crowns before his crown

Triumphantly bow down,

For pride that one more great than all draws nigh:

All souls applaud, all hearts acclaim,

One heart benign, one soul supreme, one conquering name.

From A Midsummer Holiday, London: Chatto & Windus, 1884

¹ Hauteville-House, 23 janvier [1866]. ‘Monsieur, mon fils, le traducteur de Shakespeare, est en ce moment près de moi. Il m’a fait une nouvelle lecture de votre pathétique drame de Chastelard. J’ai pu, grâce à lui, en saisir mieux toutes les beautés. Il était charmé de vous traduire après avoir traduit Shakespeare, et il sentait en vous une continuation de cette sublime poésie. Votre œuvre est au plus haut point émouvante et humaine. Elle parle à la fois au cœur et à l’âme, au cœur par la passion, à l’âme par l’idéal. Un grand succès vous est dû. Vous vous rattachez glorieusement aux grandes traditions de l’art universel, et votre talent honore la littérature contemporaine. Vous me dédiez votre belle œuvre en termes qui me touchent profondément. Recevez mon remercîment ému et cordial. Victor Hugo.’

² ‘à Swinburne. Hauteville-House, 22 sept. [1872] ô mon poëte, j’ai voulu vous écrire aujourd’hui, grand anniversaire de la république. C’est le 22 septembre que je réponds à votre ode superbe du 4 septembre. Ces deux dates fraternisent. Mon fils est près de moi ; nous vous lisons ensemble ; il me traduit Swinburne comme il a traduit Shakespeare. Quelle œuvre que vos songs before sunrise ! Votre article sur l’année terrible a excité et tenu en éveil l’attention de Paris. Vous avez lu sans doute à ce sujet le rappel et la république. Vous êtes un admirable esprit et un grand cœur. J’ai votre portrait. Voici le mien. Cher et noble poëte, je vous serre les deux mains. Victor Hugo’