Victor Hugo and Guernsey: My school years at Elizabeth College, by Jean Hugo

10th May 2019

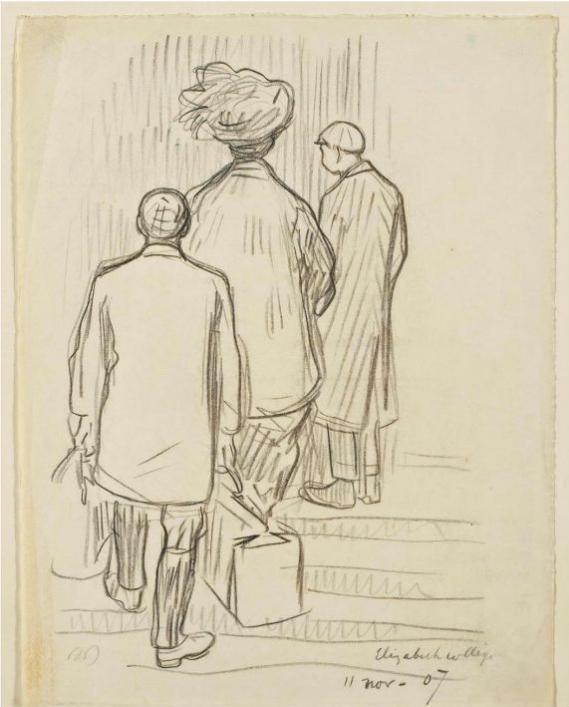

My school years at Elizabeth College, by Jean Hugo (1894-1984), from his autobiographical work, Le Regard de la mémoire, Paris: Actes Sud, 1983. Fond memories of Guernsey and characters such as 'Soapy Sam' and 'Peewee' are expressed in painterly language by the artist and great-grandson of Victor Hugo, who was a boarder at Elizabeth College. The illustration is of a drawing made by Jean's stepfather, René-Georges Hermann-Paul (1874-1940), of Jean, his mother Pauline, and the valet de chambre arriving for Jean's first term at Elizabeth College in 1907. This drawing was sold at Christie's, Paris, in 2012.

By Dinah Bott. From the French.

‘The next day, in Guernsey, on the White Rock, between Farrell and Falla, my father stood waiting for us, a silk scarf tied hastily around his neck as it was early morning. Farrell took our luggage and Falla, cracking his whip, carried us off to Hauteville House.

They gave us my great-grandmother’s room. As with all the bedrooms in the house, the windows gave out on to the street. Its dark furniture and the fabric of the tasselled curtains, peacock blue with big pink peonies, which also covered the armchairs, made you think of a Chinese garden at night.

‘Let me go back to my dark Guernsey!’ said Victor Hugo after his exile. But nothing could be less dark than this town of St Peter Port, when seen from the roads, its terraces making their way up the sides of two hills. Nothing is less dark in my memory than my years of childhood and youth spent in this island.

Yellow, pink, red, purple, green: apples, pears, plums, big bunches of grapes, gladioli, dahlias, lupins, sweet peas, the scents of the flower and fruit market fill the air, on a wide raised pavement.

White, pink, blue, purple: in the granite main hall, skate, congers, crabs lobsters, shrimps, mackerel, laid out in front of the fishwives, whose language is Norman.

Pink, red, yellow: in the shadows, too, in the stone nave, the haunches of beef and lamb and the butchers in their blue coats and striped aprons.

Yellow, pink, orange-tinted and all the rainbow hues of mother-of-pearl: the display of the shellfish vendor in his little mezzanine, opposite the French Halls and the church.

Making their way between these multi-coloured bouquets were the bakers’ white vans, the carts of the coalmen with their horses caparisoned with copper, and on market days, the crush of the crowd come in from the country parishes; some women still wore the traditional mauve dress and wide-brimmed black sun-bonnet, many men were in bowler hats, nearly all spoke Guernsey French. Even though quite a few had some physically abnormality, you couldn’t help but notice the four hunch-backed brothers from Torteval, dressed in blue serge, who never left each others’ side.

Also hard to miss was someone who was shaded a little grey, making all these bright colours stand out even more by contrast, a character we schoolboys called Soapy Sam. He usually stood on one of a low set of steps between the fruit and flower stalls and a water fountain near which the coaches and cabs used to wait. With the crown of his straw boater broken in, his small moustache and black sideburns, his shirt collar always unwashed, his extravagantly knotted tie, his old and patched jacket, his trousers too big and too long for him, his shoes worn out, and his thin cane, he was the absolute forerunner of Charlie Chaplin. He hailed the drivers, helped their customers up into their vehicles, and saluted ceremoniously as he took his tips.

Gold and silver: on the grey walls of High street and the Arcade, the golden lettering of the shops and banks, the glittering of the silver dishes in Roger the Jeweller’s window, the golden green of the verbena in Collenette the chemist’s, the white and gold of the façade of the Yacht Hotel and Le Noury the baker’s shop front.

Red and gold: the wooden Scotsman at the door of the tobacconist’s at the bottom of High Street.

Blue and red: the china statuettes, the Staffordshire figurines on the mahogany furniture in Machon the antique dealer’s in the Lower Pollet, which leads to the harbour.

Garnet red, bright yellow and red-brown: the bottles of wine, the jars of mustard and the hams you had to pass on the way up to the tearooms in Le Riches, where, sitting on the deep sofas, pretty ladies took tea with the officers of the garrison, to the sound of the violins of the Santangelo Orchestra, on tour in the islands.

Orange-tinted, yellow, pink, lilac, grey-blue: behind their araucarias, their yuccas and their magnolias, the lovely painted residences of the Grange, the faubourg Saint-Germain of Guernsey.

And finally, pink, mauve and blue: the flower-beds and the hydrangea hedges in front of the white-windowed granite cottages in the country lanes.

All this had hardly changed in six years. The painted wooden Scotsman had been bought by an antique dealer. Soapy Sam had gone but lived on in Charlie Chaplin, the four hunchbacked brothers were dead and all my schoolfellows had been killed in the war. But the rest remained, including the memories of my happy school years, spent in that big yellow ochre building with its crenellations, easily picked out from the deck of the boat well before you got into the harbour.

From the window of the study I shared with two school friends, you could see a huge and diverse panorama. To the right, you looked down the Grange, where we saw the girls whizz past on their bicycles, the cabs hurrying down to the harbour with their two-note bells ringing, after the arrival of the packet was flagged on the pole at Castle Cornet; the college headmaster leaving to go fishing, wearing his little black cap, his coat-tails flapping in the wind; the red-faced retired colonels, in their rough light-coloured clothes, making their way towards the Grange Club, and the old women returning from the market, their little round baskets full of fruit and flowers. Further down, a dark wall: the prison. Occasionally we saw a white flag raised over its roof: it was empty. Opposite us, above St James’s Church, where we sometimes went in the evening to sing old Simeon’s canticle, our view took in the harbour and the whole archipelago: the reefs, the beacons, the tower on its own amongst the waves where once upon a time a lone gunner whiled away his days, the fishing boats executing their sharp turns, the Platte-Fougère lighthouse which bellowed every time it was foggy; Herm, whose kangaroos and shells we could not, alas, make out; Jethou, whose rabbits we couldn’t see either; Sark, whose grottos carpeted with multicoloured sponges I had visited, Alderney and the Casquets which were written of by Swinburne, and far off, on a clear day, the bell-tower of Surtainville on the French coast!

It was a blessed time! My schoolfriends collected butterflies and seabirds’ eggs. We used to go to a nearby farm to watch the boar cover the sows. We bought ‘rolls’ from the baker, an enormous man with a long grey beard, always white with flour. His name was Le Poitevin, but we called him Peewee. He always spoke to me in French. He and Mrs Peewee, a sweet old dear with lovely white hair looped back from her face, treated us like their children.

As we were forced to keep to our school uniform, a regulation dark grey, navy and black tie, we kept a watchful and jealous eye on the elegance of the officers of the garrison. The colour of their clothes, mustard yellow, pepper or cinnamon, their jazzy ties, their sulphur-coloured waistcoats, we found it all dazzling. No detail escaped us: the number of buttons on their sleeves, where they kept their handkerchief, how they held their canes.’