Victor Hugo and Guernsey: a visit to Victor Hugo’s House, 1866

5th July 2018

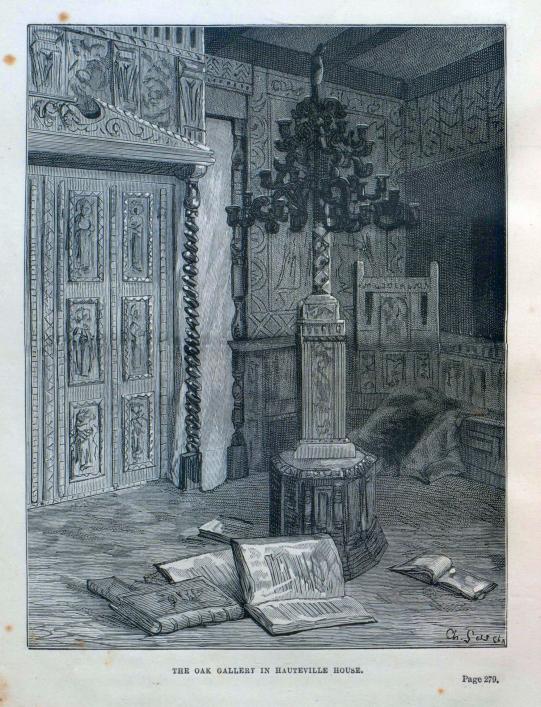

By Thomas Cave, from the North Devon Journal, September 20 1866. 'It is always interesting to trace the home and associations of an eminent author and to realize a little of the inner life of the man whose works instruct or amuse us, especially when the impress of his mind is so visibly traceable in the material objects about him. It seems as if the fanciful taste which has arranged all these materials at its will in turn receives daily promptings from its very creation.' The engraving of The Oak Gallery is by one of Hugo's favoured artists, Fortune Méaulle, from Alfred Barbou's Victor Hugo and his times, New York: Harper, 1881, in the Library Collection.

Guernsey, September 11, 1866

It occurs to me that some of your readers may be interested in a few jottings made from memory, of a visit I made to the residence of Victor Hugo, which is among the objects of interest open to travellers in this island. It is situated in St Peter’s Port, the principal or rather the only town in Guernsey, in the quarter known as Hauteville. As one toils up the granite pavement he appreciates the appropriateness of the name and realises from the patois of the islanders and the odd mingling of French and English names the old connexion which existed with the Norman Duchy, and that it is still a land of mixed races. The first sight, however, of the tall dull-looking building and the common-place ‘Hauteville House’ over the door recall one from the romantic associations of the past to the matter of fact 19th century.

Victor Hugo is with his family in Brussels arranging it is said for the publication of another work as a sequel to Les Travailleurs de la mer.

We readily gained admittance, however, and were shewn over the house by a faithful old domestic, who appears to share the social instincts of her master. The hall is divided by a singular screen of dark wood, glazed with the rough centrepieces of crown glass bearing the inscription, ‘Notre Dame de Paris, Victor Hugo.’ The first division is draped with Indian matting and tapestry; the walls and ceiling of the second are covered by a motley collection of plates and dishes, supported by red painted cross lathes, the greater portion being of the old Delph ware.

We pass by the garden entrance in to the atelier and thence to the smoking-room, where the evidences of originality are striking. The entire room is furnished with a Eastern-looking divan of Turkey carpet. On the oaken table, blackened by age, lies a copy of les Misérables, freely illustrated, and a folio volume of photographs forcibly illustrating the startling vicissitudes in Jean Valjean’s life, the teaching story of Fantine, the episode of Waterloo, the inscrutable arch-detective Javert, the tragic scene of the barricades—and Jean’s death, with Cosette and Marius kneeling before him. Near this lies Swinburne’s Chastelard, with his glowing eulogies on Victor Hugo in the dedication. The walls of this room are covered with Gobelin and Spanish tapestry with fine massive old oak carving.

Mounting next to the top of the house, we find the entire walls and balustrades covered with tapestry or drugget. Mirrors and China ornaments are placed here and there, and on each landing festooned drapery admits a subdued light, producing an effect half oriental and half French. Arrived on the upper storey we are introduced into the author’s study, a combination of attic and photographic studio, the solid sides of which are finished with the same kind of broad rude divan as that before described. The other half is covered in with glass window, only in one corner of which is an ink-stained and well-worn bracket table, where, for 10 years, Victor Hugo has written daily from early morning until noon so much that serves or excites instructs or irritates, as the temper or opinion of the reader inclines. From the transparent walls of this studio the eye rests in every direction upon a magnificent panorama. On the left is the town of St Peter Port, sloping down to the harbour, with its narrow granite-paved streets, its quaint church and spire with a bell tower placed artificially on one side; then the old harbour enclosed and as it were swallowed up by the stately new pier which runs out to sea and meets the new breakwater pushed out from Castle Cornet. This old Norman fortress which guards the island is now joined to the mainland by a fine causeway, beyond its fair outline. The background of the picture is formed of the islands of Herm, Jethou, and Sark, and the Brehon rock with single round tower rising up from the sea. On the right the high rock on which stands the modern Fort St George. A wide stretch of blue sea, with the cliffs of Saint Ouen’s Bay, Jersey, glistening in the sun far away, complete the picture. One may well conceive that the wild beauty of this scene tends to feed the powerful imagination of the gifted man. The ornaments of the study are Chinese dragons in red, green, and gold, and there is the story of Saint George and the Dragon carved in deal and painted in gaudy colours; the saint after his victory brings a dragon‘s head and presents it at the feet of a female figure, the divinity of republicanism, Liberty, or some other abstraction, who leans forward to receive it in a style suggestive either of the figures on a Chinese plate or a medieval saint.

We come next to the bedroom of M Hugo. The entrance is a hanging lamp composed of the hilt of a claymore, a brass charcoal burner inserted, and a small glass cup. His narrow embroidered couch occupies the entire end of the small apartment; at the feet a bracket table is fixed so that at will without leaving his bed and writing desk can be improvised and thoughts coming to him in the night season can be registered; a small wash-stand let into the wall is hidden by a door on which other gilt designs are traced with fanciful ingenuity; a little ink-dyed writing table and a low foot-stool were specially pointed out as the lowly seat where his brightest thoughts came to him. We descend to the old ‘Oak Gallery’ where the furniture is a compound of florid French upholstery and antique historic pieces. Here is an Austrian cabinet and seats of carved oak, which were the property of Louis the 15th; then, a bedstead of the same surmounted by a miniature Death’s head in ivory, along with rich old tapestry, and as our guide informed us, reserved for Garibaldi ‘whenever he should come.’ Below this is the Salon Rouge in which five of the panels are covered with embroidery in gold and jets, the work of Queen Christina of Sweden. Four gilt figures supporting candelabra are from the palace of the Doge; between them is placed a screen worked by the hand of Madame de Maintenon. A table of Charles II occupies the centre of the room with chairs of Henri III of France together with other heterogenous specimens, the collection of years. Upon a weird drawing by M Hugo, of the execution of John Brown, the hero of the Harpers Ferry insurrection, there is the characteristic inscription ‘Ecce Lex’. Here too, is a large black stand, supporting at each corner and ink stand long is Lamartine, Dumas, George Sand, and Hugo; underneath each drawer contains an autograph presentation of the souvenir by each. This collection was made and arranged by Madame Hugo for the last Paris exhibition, at the close of which it was purchased of her by her husband for Fr.500, which sum she presented to form the nucleus of a fund for supplying poor children with milk. This was by no means the only benevolent deed related of this family, who every week give at their own house an excellent dinner to 20 poor French, besides devoting large sums to various ways for their benefit.

A Salle à manger on the ground floor is last shown and is more like a Dutch dairy with clean tile-covered walls than a modern dining-room. Over the entrance door is carved in old oak ‘Exilium vita est’ and over the mantelpiece is an apostrophe to Liberty. It is always interesting to trace the home and associations of an eminent author and to realize a little of the inner life of the man whose works instruct or amuse us, especially when the impress of his mind is so visibly traceable in the material objects about him. It seems as if the fanciful taste which has arranged all these materials at its will in turn receives daily promptings from its very creation.

I am, my dear Sir, very faithfully yours,

Thomas Cave.