The Metivier Family

Despite many advantages, the Métivier family, which included George Métivier (1790-1881), philologist and Guernsey's 'national' poet, suffered many ups and downs, and the collection of family letters held in the Library makes entertaining reading. The woodcut is by Dr Thomas Bellamy from his Pictorial Dirctory of 1843 in the Library collection.

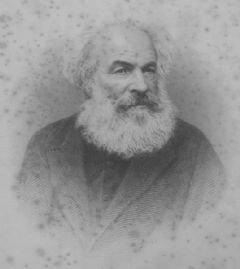

The Métivier family in Guernsey are remembered chiefly for the literary works of one of their members, George Métivier (1790-1881), philologist and poet. He wrote romantic rural poetry in Guernsey patois (he was called Guernsey’s Robert Burns by no less than Victor Hugo himself), and an invaluable dictionary of the Guernsey French language.

The family has an interesting history, full of ups and downs. We know rather more about them than is usual because the Priaulx Library has a large number of fascinating personal and business letters and documents that were left to a former Bailiff and friend of the family, Sir Edgar MacCulloch, by the advocate and Jurat William-Pierre Métivier. They cover the end of the 18th and the first 60 or so years of the 19th centuries and give a great deal of information about this family and many other Guernsey matters.

The Métivier family was part of the Huguenot nobility, being descended from a Pierre who fought for the King of Navarre in 1587, and who was ennobled by Henry IV of France after the battle of Coutras. His great-grandson, Jean de Bonnefine (b. 1662) was the ancestor of the Guernsey branch of the Métiviers.

Jean Métivier, the first of the family to reside in Guernsey,1 was a Huguenot refugee. He was a pastor in Dordrecht before taking up the position of curate at the Câtel church under another Huguenot refugee, the Reverend Isaac Babault. Isaac died in 1752; Jean married his daughter Susanna in the same year and took on his post as Rector of Câtel Church. In 1755 he married Elizabeth Carey, daughter of Nathaniel Carey and Marie Gosselin of St Peter Port. In 1757 their son Jean-Carey was born, but Jean himself died the next year.

Jean-Carey went on to become an advocate and eventually Comptrolleur. He married Esther Guille, a member of the grand Guille family that lived at the St George estate in the Câtel. In 1788 their first son, John, was born; he was followed by George (the poet), born in Fountain Street in 1790, William-Peter (Guillaume-Pierre) in 1791, Charles in 1793, and Henri-Ireland in 1795. Henri-Ireland died the next year, then Jean-Carey himself died in 1796, aged only 38. His last son, Carey Henry, was born in 1797. When George was 13, he went to live at St George with his mother and her family, and there he learnt to speak Guernsey patois.

J'vé l'ombre d'men cher p'tit grand-père,

Qui m'guette au coin du grand Mont-d'Va. [From L'Temps qui n'est pus.]

'I can see the shade of my dear little grandfather, Keeping a watchful eye on me from the corner of big Mont d'Aval.' (He was scrumping John Guille's precious apples.2)

As the Guernsey roads were virtually impassable for all but carts, Mr Guille of St George, whose grandchildren had to go to town for their schooling, had a strong horse with two panniers, and each day he brought his 4 to 5 boys to town for their lessons. This was in the young days of our present Dean and of his late brother John Guille, Bailiff; the brothers Métivier then lived with their grandparents [and two orphaned cousins] at St George.³

Some idea of St. George at that time can be gleaned from this quotation from Cecil Smith's 1879 Birds of Guernsey and the Neighbouring Islands:*

Our venerable national poet, Mr. George Métivier, has many allusions to the Oriole in his early effusions, whether written in English, French, or our vernacular dialect. It seems to have been an occasional visitor at St. George's; but in Mr. Métivier's early days the island was far more wooded than it is at present, and it is possible that the wholesale destruction of hedgerow elms and the grubbing-up of so many orchards in order to employ the ground more profitably in the culture of early potatoes and broccoli, by which the island has lost much of its picturesque beauty, may have had the effect of deterring some of the occasional visitors from alighting here in their periodical migrations." Signed "Tereus."

A short time after the appearance of this letter in the 'Star' on the 16th of May, 1878, Mr. MacCulloch himself wrote to me on the subject and said:—'I had yesterday a very satisfactory interview with Mr. George Métivier. He is now in his 88th or 89th year. He told me he was about thirteen when he went to reside with his relations, the Guilles, at St. George. There was then a great deal of old timber about the place and a long avenue of oaks, besides three large cherry orchards. One day he was startled by the sight of a male Oriole. He had never seen the bird before. Whether it was that one that was killed or another in a subsequent year I don't know, but he declares that for several years afterwards they were seen in the oak trees and among the cherries, and that he has not the least doubt but that they bred there. One day an old French gentleman of the name of De l'Huiller from the South of France, an emigrant, noticed the birds and made the remark--'Ah! vous avez des loriots ici; nous en avons beaucoup chez nous, ils sont grands gobeurs de cerises.' It would appear from this that cherries are a favourite food with this bird, and the presence of cherry orchards¹ would account for their settling down at St. George. I believe they are said to be very shy, and the absence of wood would account for their not being seen in the present day.'

In George's own words: 'Il y a dans notre premier couplet, une allusion aux sifflements du loriot (golden thrush), fameux gobeur de cerises, que le chansonnier a parfois déniché dans une vieille chênaie qui n'existe plus.'

George was sent to school in England, to learn English (this was a not uncommon motivation amongst the moneyed classes, who were conscious of their strong Guernsey accent). He studied medicine at Edinburgh University but gave it up and returned to Guernsey in 1830, publishing his first book of poems, Rimes Guernesiaises, in 1831.

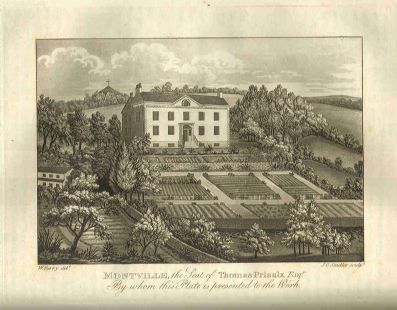

His brother, William-P., who is the author or recipient of the majority of the Library's letters, married Julia Priaulx of Montville House, Les Vardes, in 1830 and went to live at Montville, which was owned by his in-laws.

The Priaulx family had extensive business interests and although William-P. was an advocate by profession and a Jurat for 36 years, he seems to have spent a good deal of time travelling to the various parts of Europe, particularly Spain, where his merchant trading company, Métivier, Betts, and Carey (his grandmother was Elizabeth Carey), were based, and in correspondence with his partners and employees. His obituary in 1883 says: 'Previous to his being elected a Jurat, Mr Métivier was occupied in mercantile pursuits abroad, and on his return to Guernsey devoted himself to the public service. For many years [he] was the President of the States Education Committee, during which time he did active work, and aided in paving the way for the comprehensive scheme which is just about to be carried out in its entirety. [He] married a Miss Priaulx, of Montville, who predeceased him, leaving no children. For many years he has lived at Montville, with his brother-in-law, Colonel James Priaulx.' James Priaulx died only a few days after William, aged 87.

Charles, the fourth brother, based himself in Bristol as a merchant trader and seems to have also been a partner in the family company. Jean Métivier, the eldest brother, and Carey-Henry, the youngest, however, led far from straightforward lives. Jean trained as an advocate but is to be found in his thirties in Bristol, together with his mother and Carey-Henry. In 1830 he and his youngest brother took out a lease on a Georgian house in Wotton-under-Edge, in Gloucestershire, which was the centre of a historically thriving woollen trade. Carey-Henry straightaway got himself elected Mayor of Wotton (1830-32).

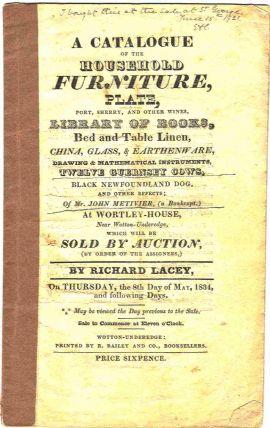

Wortley House, which is still standing, came with the lease of Monks Mills, the biggest mill complex in the area, and they took up the profession of clothier. Letters of the period and later, however, point to both brothers being less than frugal, and Carey-Henry in particular being something of a profligate. This was unfortunate, as at the very time they took on the lease of Wortley House and Mills, the woollen trade in Gloucestershire collapsed through a combination of bad management and competition, leading in 1834 to their bankruptcy, as well as that of several other prominent clothiers.

The Priaulx Library has a catalogue from the sale of the contents of the house, which someone (probably one of the family) has carefully annotated with the prices fetched on the day, as well as a more extensive handwritten list with the original prices of the goods and notes that some of the furniture belonging to Mrs Métivier had been bought back for her. Poor Esther Métivier lived long enough to see her son Carey-Henry go bankrupt again in 1838; she died in 1839 and a memorial plaque to her is to be found in the church at Wotton.

Jean spent time in Spain working for a family concern before returning to Guernsey and taking up residence in St Martin’s. He died in 1869 and was buried in St Martin’s churchyard; when George died he was buried with him. John, like his brother George, was something of an antiquarian, and in the 1850s spent a great deal of time in Normandy researching charters with links to Guernsey, which he copied and eventually had printed, exhibiting them to the Society of Antiquaries in 1856. One set of the thirty volumes were given to the Bodleian Library and the other left to Sir Edgar MacCulloch, who passed them on to the States of Guernsey.

Carey-Henry remained in Wotton until 1839, organising the Bible Society. He had married Mary Ann Cooper in 1821. In 1853 he was living at Saltford between Bristol and Bath, complaining that he has only £30 pa to live on and trying to borrow £31-8-6 from his brothers; later, in 1855, he writes of his shame at having had to raise money by 'unlawful means' and having left the debt behind. He accuses his brother Charles of slander. Amongst his four children, his son John Carey is often mentioned in the letters, firstly when a young boy, when he seems to have been a favourite, and later as a ne’er-do-well, about whom Uncles John, William-P., and Charles were constantly fretting. Charles seems to have supported him financially, but to have received very little gratitude in return. Here is a letter from John in Guernsey to John Carey, dated 8 April 1845:

My dear John,

Last Post brought me a letter from your uncle Charles the contents of which I need hardly tell you have grieved both your uncle William and myself not so much on account of your indiscretions as for the course of duplicity you have so recklessly pursued.

The very marked manner in which whilst you were here you avoided as much as lay in your power the company of your friends and especially your conduct on the day you left when instead of spending with us the short time you had to stay you were loitering about town for no other purpose than to keep away had convinced me that all was not right believe me such manoeuvres deceive no-one – Your conduct has I am sorry to say lost you the confidence of your uncle Charles – and I entreat you seriously to consider what will be your situation should you oblige him by persisting in the same course to withdraw his support from you misery and starvation will then be your question.

...

I trust the extent of your indiscretions is now known to us but should it unfortunately be otherwise conceal nothing from your Uncle Charles – sooner or later everything must be known and if after the warning you have had you should have persisted in your past course of deception your friends will be compelled to cut you off entirely.

I write - more in sorrow than in anger - It now rests with you however to determine how long I shall continue to subscribe myself, Your affectionate uncle.

Whilst in Guernsey, the Métiviers enjoyed the friendship and support of some of the most prominent families: the Careys, the Guilles, the Priaulx, the de Carterets and the Andros family, for example, to whom they were often connected by marriage and who provided many of the five sons' godparents. They also seem to have retained connections with France and another branch of the family in England. Their fortunes when they had to strike out for themselves, however, were more mixed, and thanks to the fascinating collection of documents held in the Priaulx Library, we can follow their deeds—and misdeeds—in detail for ourselves.

Should you wish to find out more about this family or view any of the material, please contact a librarian.

1 A Jean Métivier was, however, first mate on the Galley Mary, Captain James Falla, in 1751; the Métiviers were a dispersed Huguenot family. The Mary was a Guernsey privateer. 'Some notes on 18th century local shipping,' Report and Trans. of the Societe Guernsesiaise XVI (3) 1957, p. 27.

2 The Library has a letter book belonging to Jean Guille in which he mentions the fruit grown on his estate. See the Guernsey Magazine of 1884, p. 518.

3 From the Lukis MS, Edith Carey Scrapbook I, p. 95. See also the Report and Transactions of the Soc. Guernesiaise 2010, articles by Gillian Lenfestey (George Métivier) and Richard Hocart (on Jean Guille, following on from the article by the same author in Trans. XXVI (II), 2007, p. 252.)

*Birds of Guernsey and the Neighbouring Islands, Alderney, Sark, Jethou, Herm; Being a small contribution to the Ornithology of the Channel Islands, by Cecil Smith, F.Z.S., Member of the British Ornithologist’s Union, London: R.H. Porter, 6, Tenterden Street, Hanover Square, 1879.