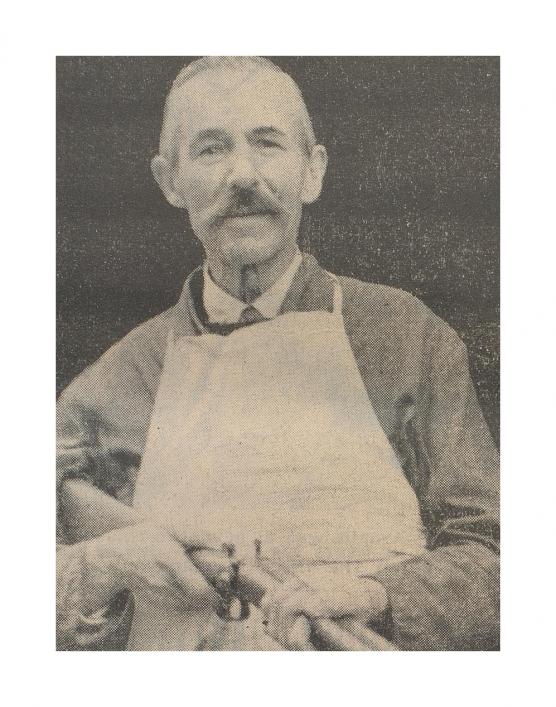

Walter Ollivier: They used to swallow the gunpowder

Ollivier the gunsmith, by Bernard Brett, from The Star November 1947. The business at 1, Tower Hill, was begun by his great-great grandfather in 1800.

See Carel Toms' Times Past, Chapter 21 for another portrait of Walter John Ollivier 1874-1965), whom Carel Toms interviewed in 1954, just after his 80th birthday. The original Toms photograph is in the Library collection (please contact the Library for more information.) The business was taken over by Collenette and then C Trotter.

At the bottom of Tower Hill is the gunsmith’s, and in 1300 at the bottom of Tower Hill was the gunsmith’s; change comes slowly to those parts.

In the shop now is an old counter which was there a good long time ago, judging by the indentations of time, the notches and cuts of ages.

On the rafters above are books, dozens of them. In the shop now is Mr W J Ollivier, 74-year old gunsmith who was born in the house above the workshop and spent 25 years of his married life there.

Changes

He looked through his glasses at me and turned a slow glance round the empty shelves which were there when they were laden with cartridges which he and his wife had hand-filled with shot and powder. His eye went over the scythes and sickels, the hammers and the scissors.

Things are changing,’ he said. ‘We don’t have iron kettles and tin kettles on those hooks now. This old counter. Oh yes, that’s been changed. I think it was my father who put this here. We’ve changed the inside of the shop a bit since I’ve been here, and I started learning here 59 years ago.

My father used to convert flint-loaders to muzzle-loaders when I first started, but there’s none of that now. Times have changed. I’ve repaired six-foot high muzzle–loaders here many a time, but times are different. There aren’t a quarter of the guns coming here for repair as came here before the war.’

Pencilled record

In the shop window is a clock made at Bristol, Connecticut, which was there in Mr Ollivier’s time, and is still going, and in the workshop behind the shop they were sharpening scythes and scissors yesterday just as they were sharpening then there in 1888, when the present Mr Ollivier began to keep a pencil-written record in a book about the number of scissors, knives, shears and scythes he sharpened yearly.

The same book still hangs by a leathern thong near the grinding machine, and in the work-shop is a plane used by Mr Ollivier’s grandfather.

But times have changed. ‘We used to grind by hand,’ Mr Ollivier told me. ‘Hour and hour at a time I used to stand, turning the wheel, and now it’s done by electricity.

Now that’s a strange thing,’ he said. ‘I went to London last year and saw an electric clock for the first time. I just don’t understand how they work.’

Mr Ollivier is keen-eyed behind his steel-framed spectacles. His hair is far from grey, and, I rather imagine, he could still be a bit of a shot. He used to shoot with the old Perseverance Air Rifle Club—they used to shoot in the cellar below Leale’s—and he is still proud of a score of 99 out of 105 with guns much inferior to the modern BSA.

600 years

I asked him if he was Guernsey through and through.

‘We’ve been here about 600 years,’ he said. ‘If we’re not Guernsey now, we never will be. There’s a contract in the family of rentes going back to 1647.’

I looked with new interest at this man of Guernsey, only gunsmith in the island, and running a gunsmith’s business establisehd here for a century and a half.

He has no-one left to keep the name of Ollivier going in the gunsmith’s trade, but he is happily training an eager newcomer called Frank Young, who has now had two years in the Tower Hill workshop. Frank is a young man and keen on the trade. ‘Mr Ollivier is teaching me all he knows about guns, and that’s a fair amount,’ he says. ‘This place will never have the same jobs to do as it used to have, but I doubt if it will ever change very much.’

It has changed in this way—that Mr Ollivier, in his time, has filled thousands and thousands of cartridges with shot and powder. ‘So has my wife,’ he said. ‘We’ve done thousands together. But those days will never return.’

No powder now

‘I don’t bother with powder now. I used to get scores of people coming in for gunpowder as a cure for boils. They’d swallow as much as would cover a sixpence—it’s an old soldier’s remedy—and they still come asking for it. No! I don’t bother with powder now.

‘They say loose powder must be kept 25 yards from the road, and when the inspectors stared coming round they insisted on electricity instead of gas—and the first inspector knew so much about it he thought lead pellets were dangerous.

‘And I’d never had any trouble before.’

The nearest establishment ever came to trouble was when a man called in and asked for a revolver. In those days they were 7s 6d each, Belgian-made.

‘Will you load it for me?’ said the man to Mr Ollivier. ‘Load it?’ said Mr Ollivier. ‘What do you want it loaded for?’ ‘Load it, load it,’ said the man.

Few guns now

‘But he didn’t get it,’ Mr Ollivier told me. ‘I wasn’t going to have him committing suicide in the shop on the cheap like that. And it might have happened. Just before, a man had gone into a gunsmith’s in Paris, asked for a gun and had it loaded, and shot himself without paying for it. No! I wasn’t going to have him doing it on the cheap with me.’

Work just now is pretty busy at the shop, but it is mostly on scissors, knives, scythes and other agricultural instruments. Very few guns are brought in. It costs £30 to £40 now for a sporting gun, as against £4 15s up to £9 before the war, and people just can’t afford the price. Second-hand guns are selling up to £40.

As for repairs, most of the guns vanished during the occupation, and some were so well hidden that they came up ‘looking just like anchors—rusted right through,’ says Mr Ollivier. ‘There isn’t the work there was in gun repairs—but other work....’ and Mr Ollivier looked around the piled-up shelves.

‘Few years yet’

‘Saws and scythes and sickles and scissors,’ he said. I’ve undone 85 pairs of scissors this morning only—but I suppose I’ll go on a few years yet. I’ll have to teach Frank the tricks of the trade. You see, he’s only been here two years.’

I could see by his expression that two years was nothing to Mr Ollivier. It is a long time since the first Ollivier set up as a gunsmith in Tower Hill—and two years more or less, in a place where change comes slowly, is no more than a couple of months.

Library Sports Folder (Green): Donation from M Martel. Photographs of inside of forge in shop, bellows, grinding wheel etc.; blank airmail letters made for Charles Trotter, photographer, Nairobi; lease of shop from Ollivier to William G R Collenette (19.07.1954); agreement re assignment of lease of shop, 03.12.1970; Plan of layout of shop showing position of ammunition storage, done for C M Y Trotter by R Vaudin, September 1970; two letters, dated 1980 and 1981, re lease. See also Carel Toms Collection. Contact the Library for further information.