Disorder in the Court, 1790

From the Gazette de l'Isle de Jersey, January 8, 1791. The autocratic Le Marchants—the Bailiff and his two sons—and their provocative behaviour. The original is in French. The illustration is from Augustin Grisier's Les Armes et le duel, 1865, from the Library collection.

News from Guernsey

'A SPECTATOR' has just sent us the account of something that occurred in the Royal Court of Guernsey, last February or March. He asks us to print it along with its potentially tragic consequences, in order to show posterity the good order that prevails in that jurisdiction, and how society should learn from it. It was unnecessary for Mr Spectator to offer us payment; we only ask for money for advertisements and notices, etc. Far from asking for payment to publish news, we are very grateful to receive any, and we are especially pleased if the news comes from Guernsey, a place so productive of great things. We ask simply that our correspondents send us their news as soon as possible, with plenty of detail, and don’t worry about style.

Here is the story:

When, in Moreau vs. Wood, the Procureur1 and Mr Métivier2 were determinedly pleading their clients’ case, neither lawyer would give an inch. The Procureur, either in a bad mood because he was worried that he was going to lose the case, or having simply run out of arguments, so forgot himself that he called Mr Métivier impertinent.3 Mr Métivier was extremely shocked by such language, and was about to call the Procureur out, but changed his mind and instead returned the insult, upon which the Procureur called him a coward. That was as far as the exchange of compliments went. Mr Métivier finished his pleading and kept his calm; but that evening he challenged the Procureur to a duel. They met the next day, with their seconds, and the business went on, following the usual rules that apply when people set out to cut each others’ throats. Luckily neither of the duellists was injured.

Another very similar quarrel between the Bailiff, his two sons and his nephew, is yet another example of the good order that reigns in the Royal Court of Guernsey. One Saturday last October, the Comptroller4 was pleading to a full courtroom on behalf of a client indicted by the Procureur, when he was interrupted several times by the Bailiff. The Comptroller was offended; the Procureur got involved; Mr Robert Le Marchant,5 one of the Jurats, had a go too; insults flew around all over the place, and that evening a duel took place between the Jurat and the Comptroller. Reports of the duel differ in some details, but agree in this: that the Comptroller received the cartel [challenge], wounded Mr Le Marchant slightly and disarmed him, and that then, (who knows what got into them), they came to blows and had to be speedily separated.6

Oh what a fine example of respect for authority,7 prudence, moderation and good order is that practised by our officials! A really excellent example to set for those people from whom they desire respect!

1 Hirzel Le Marchant (1752-93), son of the Bailiff, William Le Marchant. Two accounts of the life and deeds of William le Marchant, Bailiff, are to be found in Cecil de Saumarez' lively 'The story of William Le Marchant, Bailiff of Guernsey, 1770-1800,' Report and Transactions of the Société Guernesiaise, XVII (1965) pp. 717 ff., and Richard Hocart's life of Peter De Havilland, Peter De Havilland: Bailiff of Guernsey: a history of his life 1747-1821, Société Guernesiaise, 1997, based on De Havilland's correspondence. William Le Marchant hated Peter De Havilland, despite their family connections, and ruined any chance De Havilland had of a career as an advocate. They clashed many times.

2 Jean-Carey Métivier, father of the poet George Métivier. He married the well-to-do Esther Guille and went on to become Comptrolleur, but died in 1796, aged only 38, leaving five young sons. He fought at least two duels with Hirzel Le Marchant (Hocart, as above, p. 44).

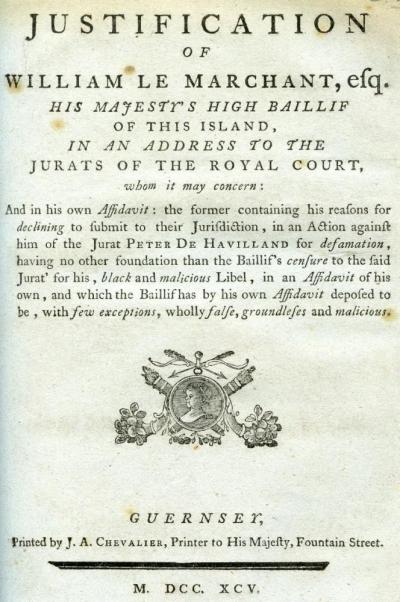

3 For a taste of such name-calling, see Le Marchant's account of Peter De Havilland's 'impudence and impertinence' in the Royal Court, and De Havilland's version of events, in Justification of William Le Marchant, esq. His Majesty's High Baillif of this island: in an address to the Jurats of the Royal Court, 1795, pp. 151 ff.

4 The Bailiff's nephew, Thomas de Saumarez.

5 The Bailiff's other son, who followed him into office.

6 In 1794 the Court ordered Le Marchant to pay De Saumarez damages of 300 livres tournois. See Hocart, as above, p. 41 ff, for details of the trivial causes of the duels between these parties; when Hirzel Le Marchant died in 1793 Peter De Havilland confessed himself overjoyed—he died, wrote De Havilland, 'to the great joy of' and 'covered with the complete execration of' the public (Hocart, p. 44).

7 French 'subordination.' A key word in Guernsey politics of the time.

William Le Marchant (1721-1809) served as a Jurat from 1754, was appointed Receiver in 1764, and held office as Bailiff of Guernsey from 1771-1800. In 1750 he was author of Histoire de l'erection originelle de l'avancement & augmentation du havre de la ville de St Pierre Port à Guernesey: avec quelques remarques....; The Rights and immunities of the Island of Guernsey, most humbly submitted to the consideration of a government in a speech of one of the magistrates of that Island to the Royal Court there.... was written in 1771, and reflects his dedication to what he regarded as the correct interpretation of the law and to the good of the island; despite his personal failings, which included corruption and forgery, he was an excellent delegate and representative of Guernsey. Réfutation d'un libelle infame, by William Le Marchant, came in 1777. In this he includes his 'posting' of Peter De Havilland of 12 June 1777, a challenge to which De Havilland refused to rise:

I the undersigned, in consequence of Peter De Havilland's insults and the answer he gave to the gentleman who relayed my challenge to him, his refusing to give me that satisfaction which every gentleman has a right to ask and to expect of another, am using this method to post him up as as the basest of Cowards, and the most outstanding Liar and scoundrel [le plus Lâche des Poltrons, & le plus Insigne Menteur de tous Belîtres].

Le Marchant's complaint to the King, and the Jurats' answers, and the Jurats' various complaints, and the Bailiff's answers, can be read at length in the Justification of William Le Marchant, esq. His Majesty's High Baillif of this island: in an address to the Jurats of the Royal Court, 1795, in the Library.